The Stamp Act of 1765 was ratified by the British parliament under King George III. It imposed a tax on all papers and official documents in the American colonies, though not in England.

Included under the act were bonds, licenses, certificates, and other official documents as well as more mundane items such as plain parchment and playing cards. Parliament reasoned that the American colonies needed to offset the sums necessary for their maintenance. It intended to use the additional tax money to pay for war expenses incurred in Great Britain’s struggles with France and Spain, and in which Britain and its 13 American colonies had been allied.

Many American colonists refused to pay Stamp Act tax

The American colonists were angered by the Stamp Act and quickly acted to oppose it. Because of the colonies’ sheer distance from London, the epicenter of British politics, a direct appeal to Parliament was almost impossible. Instead, the colonists made clear their opposition by simply refusing to pay the tax.

Prominent individuals such as Benjamin Franklin and members of the independence-minded group known as the Sons of Liberty argued that under the principle of “no taxation without representation” that was embodied in the Magna Carta of 1215, the British parliament, in which no Americans were seated, did not have the authority to impose an internal tax on the colonists.

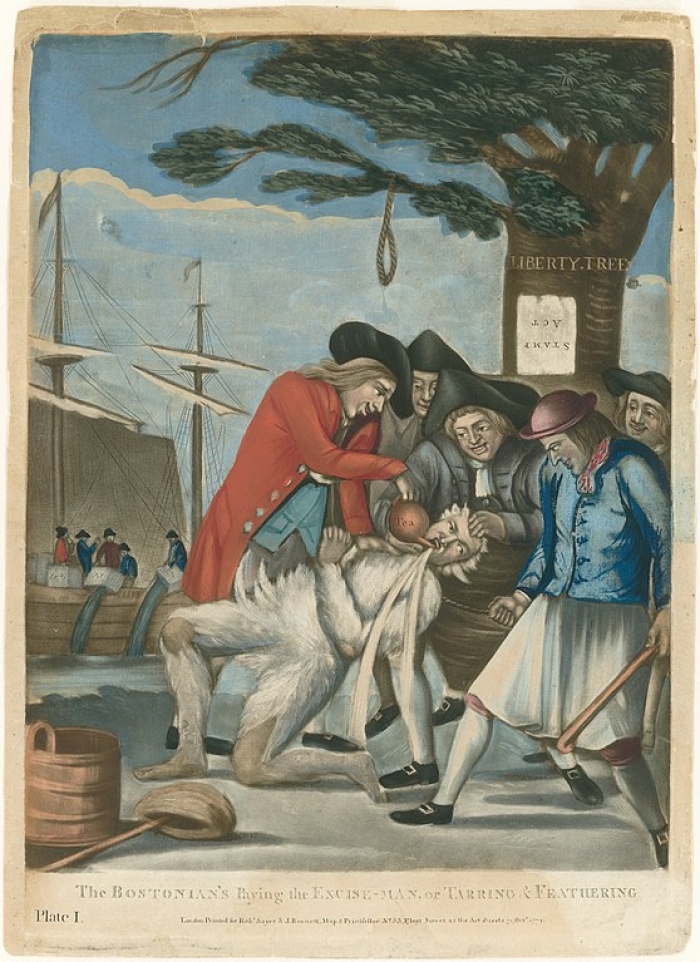

Public protest flared and the ensuing violence attracted broad attention. Tax commissioners were threatened and quit their jobs out of fear; others simply did not succeed in collecting any money. As Franklin wrote in 1766, the “Stamp Act would have to be imposed by force.” Unable to do so, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act just one year later, on March 18, 1766.

Attempts to impose other taxes such as the Townshend Duties on glass, lead, paint, paper and tea, however, provoked similar resistance. This included the famed Boston Tea Party of Dec. 16, 1773, when colonists dressed as Native American Indians threw barrels of British tea into the city’s harbor.

American separatist movement grew during protest of Stamp Act

The colonists may well have accepted the stamp tax had it been imposed by their own representatives and with their consent. However, the colonists’ emerging sense of independence — nurtured by the mother country and justified by their multiple interactions with other trading nations — heightened the colonists’ sense of indignation and feelings of injustice. Even had they submitted to it, there is little doubt that many would have been troubled by the negative impact of a tax on the free press.

Nine of the 13 colonies sent representatives to the Stamp Act Congress that met in Federal Hall in the city of New York from October 7 to October 25 of 1765. It served as a prototype for the Continental Congresses, the second of which would adopt the Declaration of Independence.

Scholars contend that the American separatist movement gained a great deal of influence as a result of its success in protesting the Stamp Act.

Stamp Act influenced constitutional safeguards, First Amendment

The act and the violence that erupted with its passage remained fresh in the young country’s memory. In addition to entrusting the power to tax in a bicameral Congress in which Americans were represented, the crafters of the Constitution were careful to include safeguards against usurpations of freedom and the violence such acts could breed. Article V provides for a constitutional amending process, allowing for changes in the laws without resort to violent revolution.

The First Amendment secures freedom of speech, the right to peacefully assemble, and the right to petition government. It also protects the freedom of the press.

This article was originally written in 2009 and updated in 2024 by John R. Vile, dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University and a history professor. Stefanie Kunze has a doctorate in political science and lectured in the Department of Sociology at Northern Arizona University.