Just as Presidents have the power to issue executive orders, they also have the power to issue proclamations. Most involve relatively routine matters, like the recognition of Women’s History Month, the Girl Scouts, and drives against deadly diseases. Although only Congress can create federal holidays, it is customary for presidents to issue official proclamations concerning holidays, especially Thanksgiving. Such proclamations date back to colonial times, when it was common for leaders to include requests for prayer and fasting.

Early presidential proclamations were at times controversial

George Washington issued two Thanksgiving Proclamations during his presidency, the first setting aside November 16, 1789, as a holiday and a second after quelling the Whiskey Rebellion. Such proclamations appear to have primarily originated from New England, but the Continental Congress adopted proclamations fairly regularly from July 20, 1775, through the Revolutionary War (see Dickson, pp. 189–191).

During the administration of John Adams, such proclamations began to have a distinctly partisan cast. Confronted with the crisis with France that resulted in part in the adoption of the Alien and Sedition Acts, Adams issued a proclamation on March 6, 1799, urging Americans to “call to mind our numerous offenses against the Most High God, confess them before Him with the sincerest penitence, implore His pardoning mercy, through the Great Mediator and Redeemer, for our past transgressions, and [pray] that through the grace of His Holy Spirit we may be disposed and enabled to yield a more suitable obedience to His righteous requisitions in time to come” (Dickson, p. 188).

This proclamation, which had been recommended by Alexander Hamilton and resembled proclamations familiar in the New England colonies, did more to stir up partisanship than to unify the nation behind his policies. Preachers often portrayed Jeffersonian Republicans and French Revolutionaries together as infidels; Jeffersonian Republicans responded that Federalists were using religious proclamations for partisan purposes.

Perhaps as a consequence of this and of his relatively strict view of the separation of church and state, Thomas Jefferson did not issue such proclamations while he was in office. Confronted by the War of 1812, James Madison did issue such proclamations, but he tried to avoid Trinitarian language and later questioned in his “Detached Memoranda” whether even the proclamations he issued had been appropriate. Presidents since Adams have avoided specifically calling upon the nation to fast and repent, although some of Abraham Lincoln’s speeches certainly conveyed the idea that the Civil War might be God’s recompense for the sins connected to slavery.

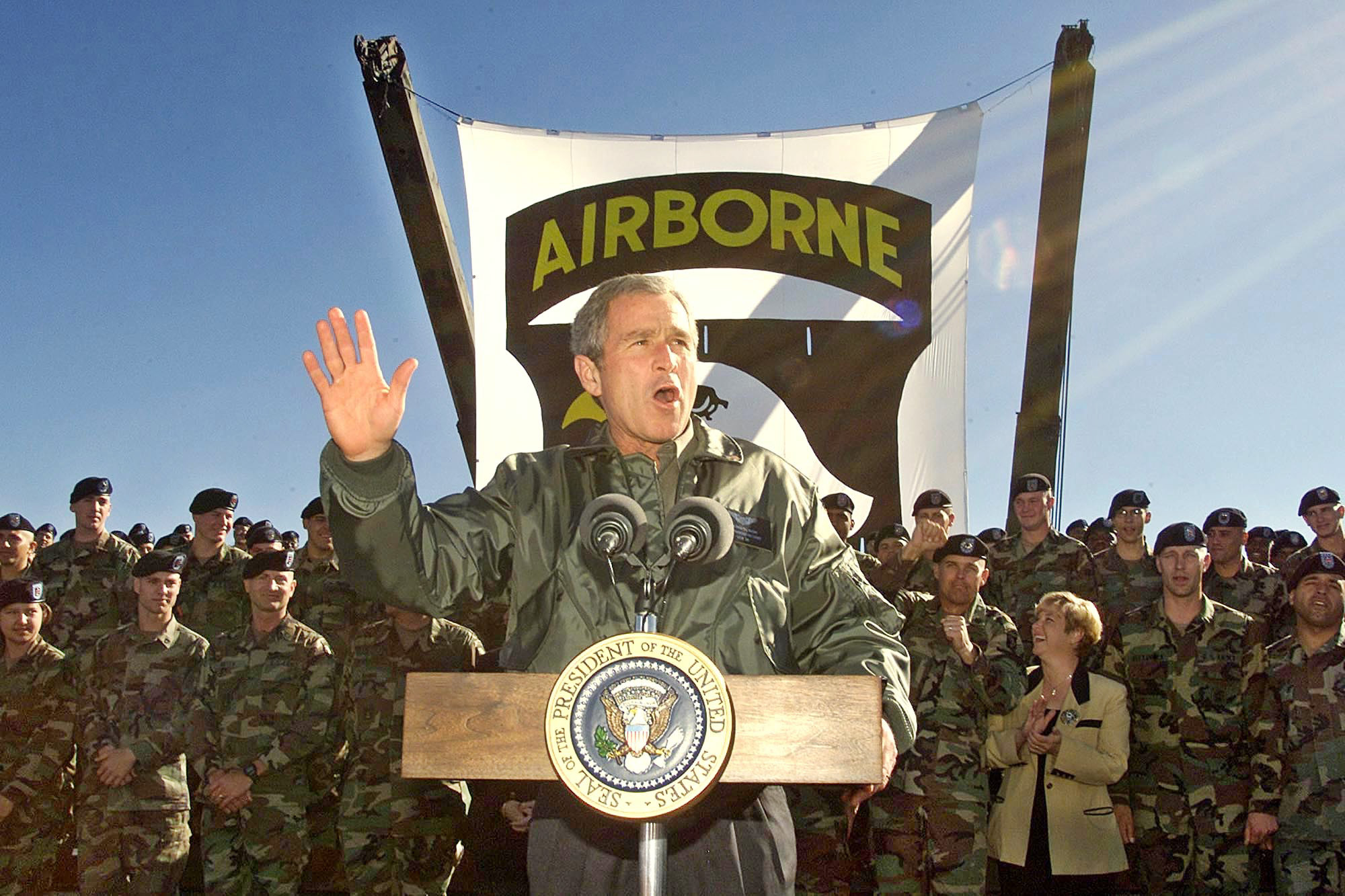

Modern generic proclamations for prayer and/or thanksgiving are generally recognized as acceptable examples of civil religion that carry no specific legal obligations or penalties. In this photo, President Richard Nixon chats with evangelist Billy Graham, Oct. 22, 1969, prior a White House breakfast to observe “National Day of Prayer.” (AP Photo/Henry Burroughs, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Modern proclamations are generally seen as civil religion

Modern generic proclamations for prayer and/or thanksgiving are generally recognized as acceptable examples of civil religion that carry no specific legal obligations or penalties. Citing earlier proclamations that dated back to George Washington, President George W. Bush’s Thanksgiving Proclamation of 2001 encouraged Americans “to assemble in their homes, places of worship, or community centers to reinforce ties of family and community, express our profound thanks for the many blessings we enjoy, and reach out in true gratitude and friendship to our friends around the world.”

Similarly, in proclaiming September 3, 2017 as a National Day of Prayer for the Victims of Hurricane Harvey and for our National Response and Recovery Efforts, President Donald J. Trump called “on all Americans and houses of worship throughout the Nation to join in one voice of prayer, as we seek to uplift one another and assist those suffering from the consequences of this terrible storm.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.