Billings Learned Hand (1872–1961), who served as a federal district and appellate judge for more than fifty years, had enormous influence on the understanding of the law in the United States, specifically of the First Amendment. Even though he was never appointed to the Supreme Court, Hand gained wide acclaim, in large part from writing features for popular magazines, including Life and Reader’s Digest, as well as for important legal decisions and writings. Legal giants, including Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., were impressed by his legal and linguistic skill.

Hand was a district and appeals judge

After graduating from Harvard Law School in 1896, Hand returned to Albany, New York, his hometown. He joined a small law firm there but later moved to New York City to practice law. Disenchanted with private practice, he joined the local Republican Party club in an attempt to obtain a federal judgeship. In 1909 President William Howard Taft appointed him as a federal district judge. In 1927 Hand was appointed to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. He was twice considered for a seat on the Supreme Court.

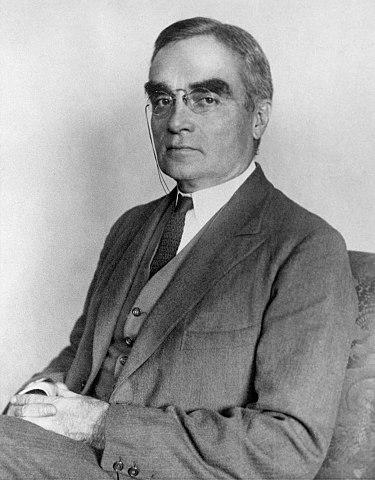

Judge Learned Hand’s most influential opinion as a district judge was in Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten (S.D.N.Y. 1917), in which he ruled against a New York City postmaster and decided that use of the Espionage Act of 1917 to prevent political dissent violated the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. In 1934, Hand set an important precedent in censorship law by ruling that James Joyce’s novel Ulysses was not obscene and could be published in the United States. (Image via Harvard University Library, public domain, circa 1910)

Hand ruled in influential First Amendment cases

Hand’s most influential opinion as a district judge was in Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten (S.D.N.Y. 1917), in which he ruled against a New York City postmaster and decided that use of the Espionage Act of 1917 to prevent political dissent violated the First Amendment’s protection of free speech. His opinion was later reversed.

In 1934, as a judge on the federal court of appeals, Hand ruled that James Joyce’s novel Ulysses was not obscene and could be published in the United States. The Ulysses decision was an important precedent in censorship law.

Hand upheld the Smith Act of 1940

Hand’s most famous ruling as an appeals judge was United States v. Dennis (2d Cir. 1950), which the Supreme Court affirmed in Dennis v. United States (1951), upholding the convictions of Eugene Dennis and other founders of the Communist Party of the United States under the Smith Act of 1940. The Smith Act, the first peacetime sedition act since 1789, made it a criminal offense to advocate or teach the doctrine of the violent overthrow of the government. Printing, publishing, or distributing materials advocating revolutionary violence or organizing a group that advocated the violent overthrowing of the government was illegal.

Hand ruled that the Smith Act was a legitimate use of congressional power. Some argue in that in Dennis he unduly disregarded the clear and present danger test. In this decision, he noted that the test was dependent upon the “gravity of the evil, discounted by its improbability.” But, he argued, this equation was “a choice between conflicting interests” and was a choice generally best left to the legislature. Indeed, only in those times when “Congress, thinking it impractical to deal with [the choice between repression and evil] specifically, makes the courts its surrogate, the choices so delegated must be treated as questions of law.” In other words, Hand was advocating judicial restraint.

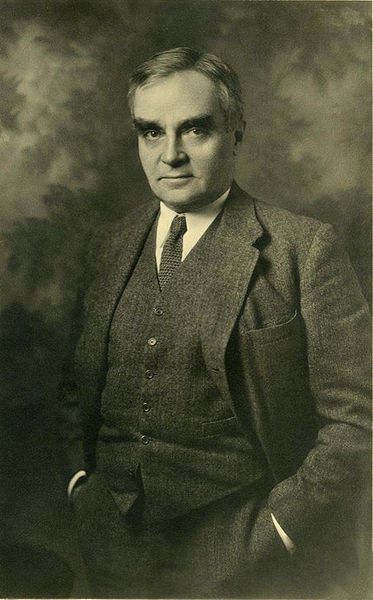

Hand’s most famous ruling as an appeals judge was United States v. Dennis (2d Cir. 1950), which the Supreme Court affirmed in Dennis v. United States (1951), upholding the convictions of Eugene Dennis and other founders of the Communist Party of the United States under the Smith Act of 1940. Hand ruled that the Smith Act was a legitimate use of congressional power. (Image via the George Grantham Bain Collection at the Library of Congress, public domain, 1924)

Hand was at odds with the Supreme Court’s individual rights expansion

Because of his views toward judicial restraint, Hand was often at odds with the Supreme Court’s expansive rulings related to individual rights under Chief Justice Earl Warren. In “The Guardians,” the final lecture in the Hand’s Holmes lecture series at Harvard on the Bill of Rights (1958), Hand outlined his reasons for not agreeing with the Warren Court’s view that individual freedoms, such as the First Amendment’s protections of free exercise of religion and freedom of the press, should be considered in a preferred position. Hand conceded that those arguing that the freedom of speech should be considered a preferred freedom worthy of increased protections have a better argument because of the hostility of the majority toward minority dissidents. But Hand also believed the legislature was more likely to tread on this freedom than were the courts, making judicial review an important protection against incursion of minority rights.

Although an advocate of judicial restraint, Hand also believed in the protections afforded by the Constitution. In “A Plea for the Open Mind and Free Discussion,” an address published in The Spirit of Liberty (1959), Hand passionately pleaded for rational reactions to dangers. He stated, “Risk for risk, for myself I had rather take my chance that some traitors will escape detection than spread . . . a spirit of general suspicion and distrust. . . .The mutual confidence on which all else depends can be maintained only by an open mind and a brave reliance upon free discussion.”

This article was originally published in 2009. Tobias T. Gibson is the John Langton Professor of Legal Studies and Political Science at Westminster College in Fulton, MO.