John Marshall Harlan II (1899–1971) served on the Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. He was a principal architect of First Amendment jurisprudence in many areas, including obscenity law, freedom of association, expressive conduct, and offensive speech.

Born in Chicago, Harlan was named for his grandfather, John Marshall Harlan I, who also served on the Supreme Court. He graduated from Princeton University in 1920, studied at Oxford, and earned a law degree from New York Law School in 1924. His career as an attorney in a prestigious Wall Street law firm was interrupted by service in World War II. He represented philosopher Bertrand Russell in a First Amendment case in which Russell had been barred from teaching at City College in New York because of his controversial views. However, he more commonly represented corporate clients.

Harlan had served on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals for eight months when President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed him to replace Justice Robert H. Jackson on the Supreme Court.

Harlan’s belief in judicial restraint influenced his First Amendment opinions

Harlan believed strongly in the Constitution’s structural limitations, particularly the doctrines of federalism and separation of powers. Those principles, he wrote,“lie at the root of our constitutional system” and must be considered in interpreting the Bill of Rights. This belief in judicial restraint had a powerful effect on Harlan’s opinions, including his First Amendment jurisprudence.

Harlan rejected the notion that the Fourteenth Amendment “incorporated” the Bill of Rights — including the First Amendment — to apply to the states. He did believe that the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause embraced the general principle of free speech, although he viewed Fourteenth Amendment constraints on the states to be less stringent than those that the First Amendment imposed on the federal government.

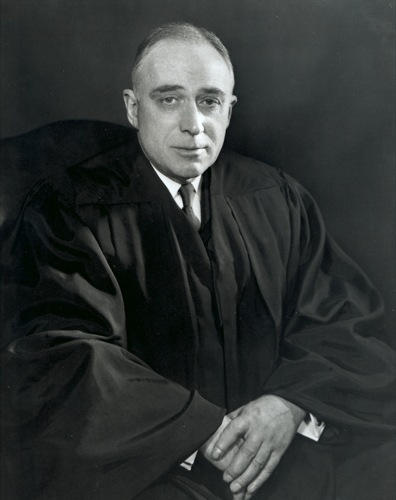

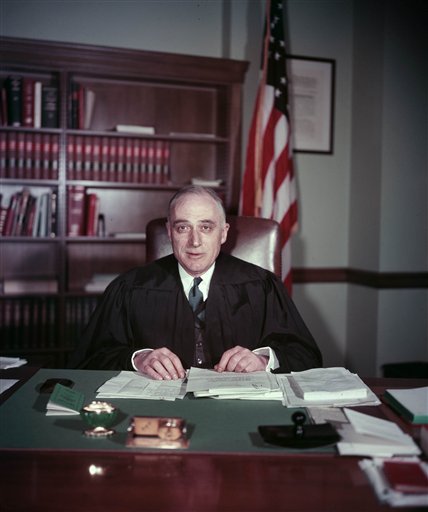

Newly confirmed Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan II, is shown seated at his desk in judicial robes in 1955. During the early part of his tenure on the Court in particular, Harlan was viewed as a “balancer” in First Amendment cases. This view of Harlan as a balancer who often deferred to the government’s interest against First Amendment rights was solidified with his last opinion on the Court, a dissent in the Pentagon Papers case. In that case, New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), Harlan would have deferred to the government, permitting it to enjoin — at least briefly — the publication of the Pentagon Papers. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Harlan’s approached obscenity law through his federal-state distinction

Harlan’s federal-state distinction clearly manifested itself in his approach to obscenity law. In two companion cases, Roth v. United States (1957) and Alberts v. California (1957), Harlan was the only justice to vote to reverse federal convictions for mailing obscene materials in Roth, while upholding a California obscenity law in Alberts. Harlan reasoned that because the federal government had no explicit power to regulate sexual morality, it could use its postal power only to regulate “hardcore” pornography. In contrast, because the states bore “direct responsibility for the protection of the local moral fabric,” Harlan would have permitted state governments to regulate sexually explicit speech as long as they did not reach results “wholly out of step with current American standards.”

Harlan reiterated and refined these views in many obscenity cases after Roth, including his majority opinion in Manual Enterprises v. Day (1962), ruling that a homoerotic magazine was not obscene, and a dissent in Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966), where the Court ruled that a book by John Cleland was not obscene. He later referred to the “intractable obscenity problem” in Ginsberg v. New York (1968), where the Court upheld a conviction for pandering of obscenity.

Harlan was a balancer in First Amendment cases

During the early part of his tenure on the Court in particular, Harlan was viewed as a “balancer” in First Amendment cases — especially regarding those involving communism — in contrast to the “absolutists,” such as Justices Hugo L. Black and William O. Douglas. Contemporary observers viewed Harlan’s balancing as less speech protective than Black’s absolutism.

Two cases that exemplify this view are Barenblatt v. United States (1959), and Konigsberg v. State Bar (1961). In both cases, Harlan wrote for 5-4 majorities over bitter dissents from Justice Black. In balancing the government’s interests against an individual’s speech rights, Harlan concluded that the government had the right to inquire about an individual’s alleged Communist Party membership — in Barenblatt in the context of a House Un-American Activities Committee subcommittee hearing and in Konigsberg as a condition of state bar admission.

This view of Harlan as a balancer who often deferred to the government’s interest against First Amendment rights was solidified with his last opinion on the Court, a dissent in the Pentagon Papers case. In that case, New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), Harlan would have deferred to the government, permitting it to enjoin — at least briefly — the publication of the Pentagon Papers.

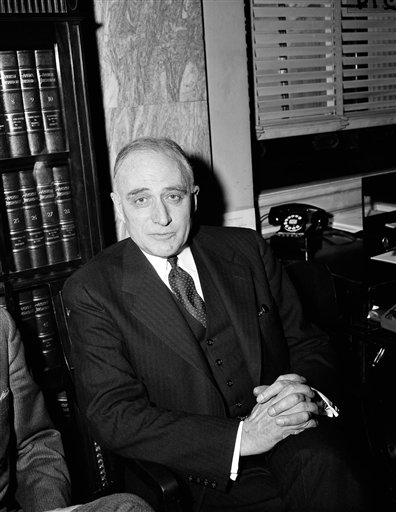

Judge John Marshall Harlan II in 1955. Notwithstanding Harlan’s reputation for deferring to the government in free speech cases, his legacy is far more complex, and he often wrote in defense of important First Amendment values.Harlan was adamant about protecting offensive speech when it implicated core First Amendment values. In Cohen v. California (1971), he reversed a criminal conviction of a man for wearing a jacket with the words “Fuck the Draft” written on it. Harlan’s opinion in Cohen, which contains the memorable line “one man’s vulgarity is another man’s lyric,” survives today as one of the most enduring statements of the fundamental First Amendment principle that any governmental attempt to sanitize or otherwise regulate public discourse is incompatible with a free society. (AP Photo/Charles Gorry, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Harlan protected offensive speech

Notwithstanding Harlan’s reputation for deferring to the government in free speech cases, his legacy is far more complex, and he often wrote in defense of important First Amendment values. For example, he wrote the Court’s opinion holding that the government could not prohibit the abstract advocacy of violent overthrow of the government in Yates v. United States (1957), the first time the Court reversed the convictions of communists under the Smith Act of 1940. In NAACP v. Alabama (1958), he wrote the Court’s first opinion holding that freedom of association is part of the First Amendment. In Garner v. Louisiana (1961), he was the only justice to recognize that a sit-in by black patrons at a segregated lunch counter could be viewed as expressive conduct protected by the First Amendment.

Harlan was adamant about protecting offensive speech when it implicated core First Amendment values. In Cohen v. California (1971), he reversed a criminal conviction of a man for wearing a jacket with the words “Fuck the Draft” written on it. Harlan’s opinion in Cohen, which contains the memorable line “one man’s vulgarity is another man’s lyric,” survives today as one of the most enduring statements of the fundamental First Amendment principle that any governmental attempt to sanitize or otherwise regulate public discourse is incompatible with a free society.

This article was originally published in 2009. Anuj C. Desai is the William Voss-Bascom Professor of Law at the University of Wisconsin, where he teaches in both the Law School and the iSchool. Among his classes are those in First Amendment, Intellectual Freedom, and Cyberlaw. He has published numerous articles on topics related to the First Amendment, including in the Stanford Law Review and Federal Communications Law Journal. Prior to entering academia, Professor Desai practiced law with the Seattle, Washington firm of Davis Wright Tremaine, where his practice included a variety of First Amendment-related matters.