Stanley F. Reed (1884–1980) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court who served from 1938 until his retirement in 1957.

He probably is best known in First Amendment circles for authoring a dissenting opinion in the establishment clause case of McCollum v. Board of Education (1948). He also is the last justice on the Supreme Court who never graduated from law school.

Reed was last Supreme Court justice to never graduate law school

Born in Macon County, Kentucky, Reed earned his undergraduate degree from Kentucky Wesleyan University in 1902. He then attended Yale University, where he earned another bachelor’s degree. He then entered law school at the University of Virginia before transferring to Columbia. Ironically, Reed never graduated law school, becoming the last justice to serve on the Court who never graduated law school.

He earned admission to the Kentucky bar in 1910 and practiced law in Maysville. He began his political career with two terms in the Kentucky General Assembly before serving his country in World War I. After the war, Reed returned to private practice and achieved significant success as a corporate lawyer.

President Herbert Hoover appointed him general counsel of the Federal Farm Board in 1929. A few years later, he headed up the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. President Franklin D. Roosevelt then appointed Reed as U.S. Solicitor General in 1935. He served in that capacity until Roosevelt nominated him to the Supreme Court.

Justice Reed often sided with government in free-speech cases

In free-speech cases, Reed often sided with the government but not always.

He authored the Court’s decision in Winters v. New York (1948), invalidating a New York obscenity law that sought to prohibit publications depicting criminal deeds, bloodshed, lust or crime. In oft-cited language, Reed declared: “What is one man’s amusement, teaches another’s doctrine.” Reed and his colleagues in the majority deemed the law too vague to withstand constitutional scrutiny.

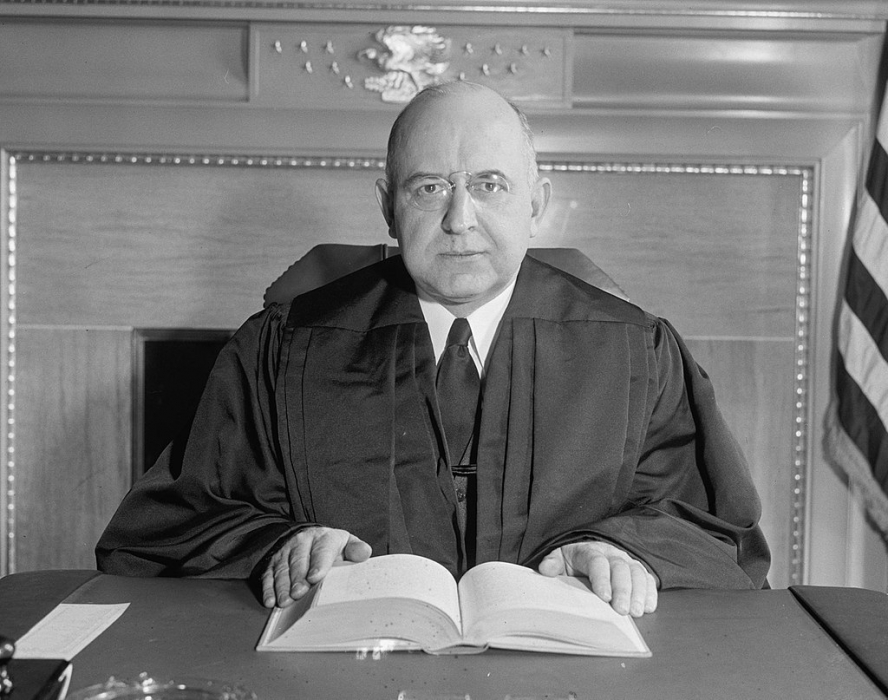

In the presence of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Joseph P. Kennedy, left, takes the oath of office to be ambassador to Great Britain in1938. Administering the oath in the president’s office is Associate Justice Stanley F. Reed of the Supreme Court. Reed was the last justice to not graduate from law school. (AP Photo/Charles Gorry, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Reed rejected claims of Jehovah’s Witnesses

Reed wrote a couple of opinions that rejected the First Amendment claims of Jehovah’s Witnesses, a religious liberty group that often prevailed as Supreme Court litigants. However, Reed seemed to show solicitude for the interests of government officials in maintaining order and control.

He authored the majority opinion in Poulos v. New Hampshire (1953), upholding the conviction of a Jehovah’s Witness who conducted a religious meeting in a public park without obtaining a license. Reed wrote that “[t]he principles of the First Amendment are not to be treated as a promise that everyone with opinions or beliefs to express may gather around him at any place and at any time a group for discussion or instruction.”

He also authored the Court’s majority opinion in Breard v. Alexandria (1951), upholding an Alexandria, Louisiana, ordinance that prohibited people from going door-to-door without first obtaining the consent of the homeowners. “By adjustment of rights, we can have both full liberty of expression and an orderly life,” Reed wrote.

Reed dissented in another Jehovah’s Witness case, Marsh v. Alabama (1946). The majority of the Court ruled that a private company-owned town could not criminalize the distribution of religious literature on its streets. Reed dissented, writing: “This is the first case to extend by law the privilege of religious exercises beyond public places or to private places without the assent of the owner.”

Reed: ‘This does not mean the freedom is beyond all control’

The U.S. Supreme Court is seen gathered at the White House in 1942. From left: Robert E. Jackson, Frank Murphy, William Douglas, Felix Frankfurter, Stanley Reed, Hugo Black, Owen J. Roberts and Chief Justice Harlan Stone. Reed often sided with the government in First Amendment cases. (AP Photo, reprinted with permission.)

Another significant free-speech opinion authored by Reed was Kovacs v. Cooper (1949). Writing for the majority, Reed upheld a Trenton, New Jersey, ordinance prohibiting the use of sound trucks for advertising or other purposes.“City streets are recognized as a normal place for the exchange of ideas by speech or paper,” Reed wrote. “But this does not mean the freedom is beyond all control.”

Reed authored a short concurring opinion in Joseph Burstyn v. Wilson (1952), in which the Court recognized that film was a medium of speech protected by the First Amendment. In his short concurring opinion, Reed wrote: “This film does not seem to me to be of a character that the First Amendment permits a state to exclude from public view.”

Reed rejected ‘wall of separation’ in church-state issue

In the religious liberty arena, Reed dissented in the aforementioned McCollum v. Board of Education. A majority of the Court determined that an Illinois law allowing public school students to receive religious education with the permission of their parents on school grounds violated the Establishment Clause. Reed disagreed, famously writing that “[a] rule of law should not be drawn from a figure of speech.”

Reed referred to the Court invoking Thomas Jefferson’s “wall of separation” metaphor in its Establishment Clause jurisprudence. To Reed, the practice invalidated by his colleagues was one supported by “well-recognized and long-established practices.”

Reed retired from the Court in 1957 but often served as a judge on various federal appeals courts and the U.S. Court of Claims.

He died in 1980 at the age of 95.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2019.