In Rabe v. Washington, 405 U.S. 313 (1972), the Supreme Court reversed the obscenity conviction of the manager of a drive-in movie theater in Richland, Washington.

Drive-in manager argued movie with sexual scenes was protected by the First Amendment

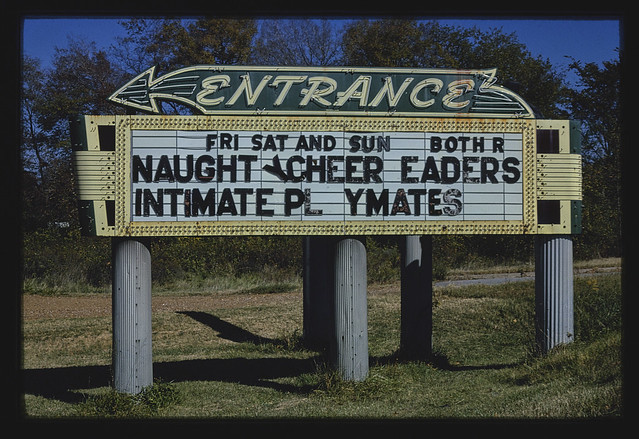

William Rabe was convicted under Washington’s anti-obscenity law after a police officer viewed the film Carmen Baby, which included sexually frank scenes, from outside the theater’s fence. Rabe contended that the material was not obscene but rather constituted First Amendment–protected expression.

Washington’s high court, applying the Supreme Court’s test for obscenity in Roth v. United States (1957), did not consider the film obscene “if the viewing audience consisted only of consenting adults.” This latter consideration, however, prompted the state court to uphold Rabe’s conviction because the “context of its exhibition” rendered the movie obscene [italics in original].

Court said state obscenity law didn’t give ‘fair notice’ to film exhibitors

The Supreme Court reversed in a per curiam opinion, finding that the state’s law did not include context in its definition of obscenity. The statute failed to give “fair notice” to film exhibitors, like Rabe, as to what was prohibited and the criminal liability they faced for showing sexually explicit films.

Chief Justice Warren E. Burger concurred in the decision but stressed that Carmen Baby or other public displays involving nudity or sexual activities “are not significantly different from any noxious public nuisance.”

Narrowly drawn statutes aimed at protecting the public, especially juveniles or adults unwilling to view the material, he opined, “involve no significant countervailing First Amendment considerations.”

Issue of public nuisance resurfaced later in secondary effect doctrine

Burger’s dicta regarding public nuisances later made their way to the Supreme Court in Erznoznik v. City of Jacksonville (1975). Jacksonville forbade any drive-in theater from showing films containing nudity if they were visible from public streets or places. The Court struck down the ordinance because it discriminated on the basis of content of the films and was impermissibly broad in its attempt to protect children or as a traffic regulation.

As drive-in theaters disappeared from America’s landscape, the issue of public nuisance resurfaced in the Supreme Court’s development of a “secondary effects doctrine” in its review of local zoning policies controlling the location of adult-oriented businesses, for example, Young v. American Mini Theatres (1976) and FW/PBS, Inc. v. City of Dallas (1990).

This article was originally published in 2009. Roy B. Flemming is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Political Science at Texas A&M University.