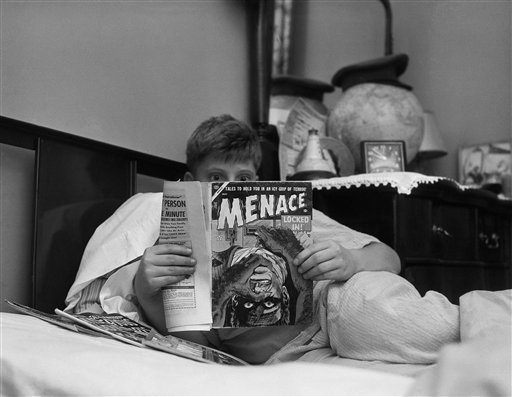

The Supreme Court in Butler v. Michigan, 352 U.S. 380 (1957) unanimously held that a Michigan law violated the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. The law made it illegal to sell printed material thought to be obscene because of its potentially harmful influence on youths.

Law made it illegal to sell printed material that could harm youths

Section 343 of the Michigan penal code made it illegal to sell to an individual “any book, pamphlet, or other printed paper or other thing, containing obscene language, or obscene prints, pictures, figures or descriptions tending to the corruption of the morals of youth, or any newspapers, pamphlets or other printed paper devoted to the publication of criminal news, police reports, or criminal deeds.”

Butler sold book that could corrupt youths

Alfred E. Butler was convicted of violating two parts of the law after he sold a book to a police officer. At Butler’s trial, the judge found that the book in question contained “obscene, immoral, lewd, lascivious language, or descriptions, tending to incite minors to violent or depraved or immoral acts, manifestly tending to the corruption of the morals of youth.”

Court said law was overbroad and violated the First Amendment

Justice Felix Frankfurter, who announced the decision in Butler, asserted that the state had too broadly defined its power in attempting to promote the general good.

He found it disturbing that in trying to protect children, the Michigan law limited grown men and women from accessing materials that may be appropriate for them. This would result in the adult population of Michigan only reading material fit for children.

Frankfurter thus concluded that the statute was not reasonably restricted to the evil it was meant to stop. The Court ruled, therefore, that the Michigan law’s overbreadth arbitrarily curtailed freedom of press — an individual liberty protected by the First Amendment and the due process clause of the 14th Amendment — rendering it unconstitutional.

This article was originally published in 2009. Tom McInnis earned a Ph.D. from the University of Missouri in Political Science in 1989. He taught and researched at the University of Central Arkansas for 30 years before retirement. He published two books and multiple articles in the area of civil liberties and the American legal system.