In United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968), the Supreme Court upheld a federal law prohibiting the knowing mutilation of draft cards, rejecting the First Amendment arguments of an anti-war protester.

Of more lasting importance to First Amendment jurisprudence, the Court created the O’Brien test for determining whether expressive conduct or symbolic speech merits First Amendment protection.

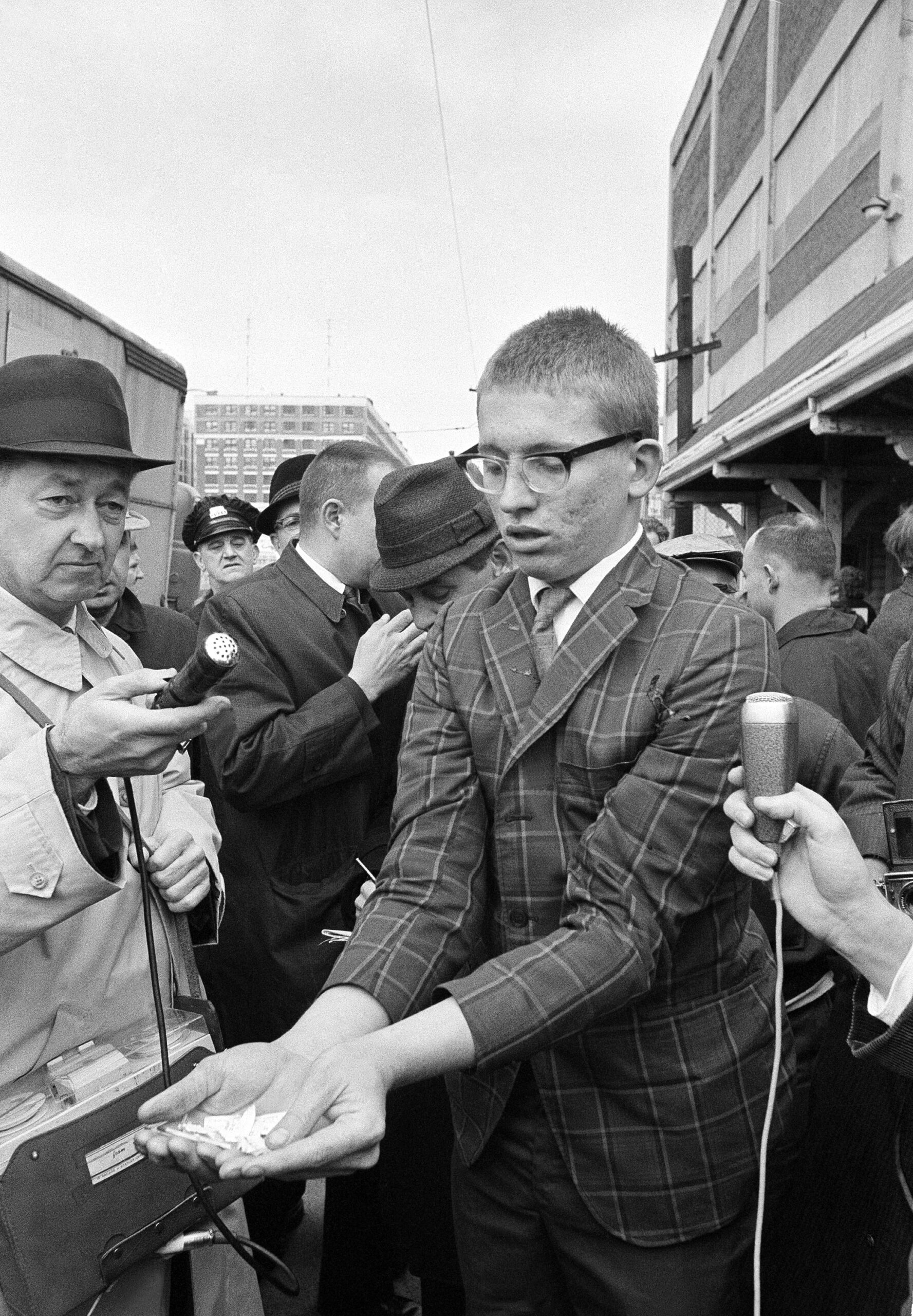

Anti-war protester says law against draft card burning violates First Amendment speech rights

In 1965 Congress amended the Selective Service Act to prohibit the knowing mutilation of draft cards. During the debate, a few members of Congress expressed their view that the purpose of the law was to silence an avenue of expression for anti-Vietnam War protesters. In March 1966, David Paul O’Brien and three other men burned their draft cards in front of a South Boston courthouse to express their anti-war beliefs. O’Brien contended that even if the law is considered valid on its face it was unconstitutional as applied to him because the law punished him for his antiwar expression.

A federal district court rejected O’Brien’s First Amendment arguments and convicted him. The appeals court then ruled that the 1965 amendment violated the First Amendment by singling out persons engaged in public protests. However, the court upheld O’Brien’s conviction under another statute. Both O’Brien and the government appealed to the Supreme Court, which granted review — presumably to clear up a conflict in the circuits (two other circuits had upheld the 1965 law).

The Court ruled 7-1 (Justice Thurgood Marshall did not participate) that the law did not violate the First Amendment because it furthered the government’s important interests in a smoothly functioning draft selection system.

Court establishes O’Brien test for laws that impact expressive conduct

For the majority, Chief Justice Earl Warren established a test for determining whether laws that impact expressive conduct pass constitutional scrutiny.

Warren wrote, “We think it clear that a government regulation is sufficiently justified if it is within the constitutional power of the Government; if it furthers an important or substantial governmental interest; if the governmental interest is unrelated to the suppression of free expression; and if the incidental restriction on alleged First Amendment freedoms is no greater than is essential to the furtherance of that interest.”

Court finds draft card law served important government interest

After applying this test, Warren determined that Congress had the power to pass the law. The law served many functions related to the efficient operation of the draft system and was “limited to the noncommunicative aspect of O’Brien’s conduct.” Further, Warren noted, “no alternative means that would more precisely and narrowly assure the continued availability of issued” draft cards existed.

Warren also rejected the view of congressional legislators who argued that the law was designed to silence anti-war protesters. Warren noted that only a few legislators made such comments and that many other legislators may have voted for the law for other reasons. “What motivates one legislator to make a speech about a statute is not necessarily what motivates scores of others to enact it, and the stakes are sufficiently high for us to eschew guesswork.”

Justice John Marshall Harlan II wrote a short concurrence, emphasizing that the “crux” of the decision was the four-part test. He added that even if a law satisfied an O’Brien test, a law could still violate the First Amendment if it “prevent[ed] a speaker from reaching a significant audience with whom he could not otherwise lawfully communicate.”

Justice William O. Douglas filed a lone dissent, believing that the case presented another opportunity for the Court to address “whether conscription is permissible in the absence of a declaration of war.”

The Court has employed the O’Brien test in a variety of First Amendment cases, even one upholding a public indecency law applied to nude dancing (Barnes v. Glen Theatre, Inc., 1991). In the flag-burning decision Texas v. Johnson (1989), the Court distinguished O’Brien because a majority found that the Texas flag desecration law was related to the suppression of free expression.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017).