In City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997), the Supreme Court ruled that Congress did not have unlimited power to enact legislation to expand First Amendment free exercise rights through its enforcement powers in Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, the amendment through which the First Amendment is applied to the states.

San Antonio church denied permit to enlarge building

The archbishop of San Antonio, Texas, had applied for a building permit to expand a Catholic church in Boerne, Texas, but the city denied the request because of an ordinance barring the alteration of historical landmarks.

The archbishop then filed suit against the local zoning authorities, claiming that by refusing to allow the church to enlarge its building, the city violated the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA).

Archbishop sued under RFRA

Congress had enacted RFRA to reverse the Supreme Court’s ruling in Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990). In Smith, two Native American church members had been dismissed from their jobs as employment counselors for using peyote. They sued, arguing that the free exercise clause of the First Amendment protected their right to smoke peyote as part of their religion.

The Supreme Court upheld the Oregon law and ruled that such neutral laws of general applicability are not unconstitutional even if they affect religious practices. In ruling for the state, the Court refused to apply its prior standard requiring the state to offer a compelling justification for the law.

RFRA required government to show compelling interest for religious restriction

Passed with overwhelming congressional approval, RFRA reinstated the compelling state interest test in free exercise cases.

RFRA provided that the government may not “substantially burden” a person’s exercise of religion unless it can show that it has a “compelling governmental interest” and the law is “the least restrictive means” to achieve its goal.

In passing the law, Congress relied on its authority under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to enforce Section 1 of the amendment “by appropriate legislation.”

Supreme Court invalidated RFRA

In Boerne, the district court held that RFRA was unconstitutional and ruled in favor of the city.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and upheld the law.

In a divided 6-3 ruling, the Supreme Court reversed the Fifth Circuit. The majority based its decisions on the principles inherent in the separation of powers among the three branches of government and chided Congress for exceeding its constitutional authority under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

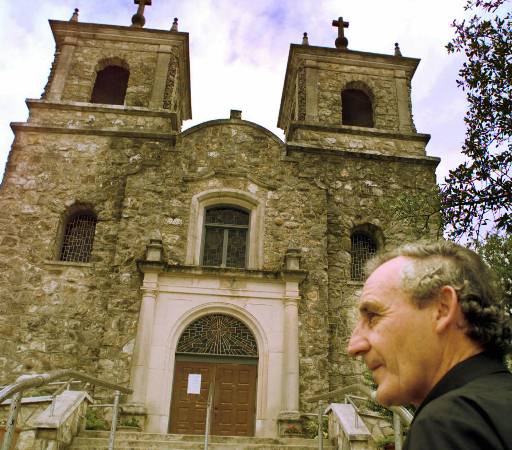

Rev. Anthony Cummins, pastor of St. Peter the Apostle Church, walks in front of the church in Boerne, Texas, Wednesday, June 25, 1997. The Supreme Court today struck down the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act involving the Texas case between the city of Boerne and the local Catholic parish. The church invoked the 1993 law after the city thwarted its attempt to tear down part of a sanctuary and build an addition because the 70-year-old architectural imitation of a Spanish mission is located in Boerne’s historic district. (AP Photo/LM Otero, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court said Congress had violated separation of powers

The Court acknowledged that Section 5 grants Congress the power to enforce rights guaranteed in Section 1, but cautioned that its power to do so is limited by the Supreme Court’s superior position in constitutional interpretation. Echoing the words of former Chief Justice John Marshall, the Court reminded Congress that the final authority in determining the boundaries of legislative power under the Constitution resides in the judiciary.

Congress had argued that RFRA was “appropriate legislation” because it prevented states from infringing on the right of free exercise guaranteed in the First Amendment and applied to the states by the Fourteenth.

The Court explained that although Section 5 allows Congress to enforce existing laws, it does not permit Congress to alter the meaning of a constitutional provision, such as, in this case, Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Congress cannot impose a remedy more stringent than the original

Conceding that it is often difficult to determine whether the legislature is enforcing existing rights or creating substantive rights, the Court established a test to determine the constitutionality of Section 5 legislation: “there must be a congruence and proportionality between the injury to be prevented or remedied and the means adopted to that end.”

To meet this standard, Congress must first find that the state had committed constitutional abuses. After making such a finding, however, the legislature may not impose a remedy that is more stringent than the one that existed previously.

The Court held that RFRA failed this test. By requiring states to justify laws affecting religious practices with a compelling state interest, contrary to the Court’s ruling in Smith, RFRA had altered the substantive meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, thus exceeding Congress’s enforcement power under Section 5.

The decision invalidated RFRA as it applied to state and local governments, but not necessarily to the federal government.

Congress responded to the Boerne decision by drafting a narrower religious liberty law, called the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000.

This article was originally published in 2009. Susan Gluck Mezey is a professor emeritus of political science at Loyola University Chicago; she holds an M.A. and Ph.D. from Syracuse University and a J.D. from DePaul University. She has published in the area of minority group policies and the federal courts. Her recent books include: Transgender Rights: From Obama to Trump (2020); Beyond Marriage: Continuing Battles for LGBT Rights (2017); Elusive Equality: Women’s Rights, Public Policy, and the Law, 2d Ed. (2011); Gay Families and the Courts: The Quest for Equal Rights (2009); Queers in Court: Gay Rights Law and Public Policy (2007); and Disabling Interpretations: Judicial Implementation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (2005).