The public forum doctrine is an analytical tool used in First Amendment jurisprudence to determine the constitutionality of speech restrictions implemented on government property. Courts employ this doctrine to decide whether groups should have access to engage in expressive activities on such property.

Roberts originated the public forum doctrine

Most scholars trace the lineage of the public forum doctrine to Justice Owen J. Roberts’s opinion in Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization (1939), in which he wrote: “Wherever the title of streets and parks may rest, they have immemorially been held in trust for the use of the public and, time out of mind, have been used for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions. Such use of the streets and public places has, from ancient times, been a part of the privileges, immunities, rights, and liberties of citizens.”

First Amendment scholar Harry Kalven Jr. wrote of the concept in a law review article in 1965 titled “The Concept of the Public Forum: Cox v. Louisiana.” The term public forum, however, did not appear in First Amendment cases until the 1970s, and public forum doctrine did not appear until the 1980s.

The Supreme Court used the term public forum frequently in the 1970s. In Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad (1975), the Court ruled that city officials of Chattanooga, Tennessee, violated the First Amendment by prohibiting the production of the rock musical Hair in public facilities. The Court wrote that the city-owned theaters were “public forums designed for and dedicated to expressive activities.” In this photo, the cast of “Hair” performs for some 400 prisoners of the Women’s House of Detention on Rikers Island in New York City, Oct. 19, 1971. (AP Photo/Jim Wells, used with permission from the Associated Press)

The term public forum was used frequently in the 1970s

The Supreme Court used the term public forum frequently in the 1970s. In Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad (1975), the Court ruled that city officials of Chattanooga, Tennessee, violated the First Amendment by prohibiting the production of the rock musical Hair in public facilities. The Court wrote that the city-owned theaters were “public forums designed for and dedicated to expressive activities.” In Greer v. Spock (1976), the Court rejected a First Amendment challenge to speech restrictions on a military base, writing “it is . . . the business of a military installation . . . to train soldiers, not to provide a public forum.”

White explained three categories of government property

In the 1980s, the Court articulated the contours of the public forum doctrine in Perry Education Association v. Perry Local Educators’ Association (1983). In Perry, Justice Byron R. White explained that there were three categories of government property for purposes of access for expressive activities.

- Traditional, or quintessential, public forums;

- limited, or designated, public forums;

- and nonpublic forums.

In the first, “quintessential public forums, the government may not prohibit all communicative activity,” White wrote, explaining that content-based restrictions on speech were highly suspect.

The second category was designated, or limited, public forums. “Although a state is not required to indefinitely retain the open character of the facility, as long as it does so it is bound by the same standards as apply in a traditional public forum,” White explained. “Reasonable time, place, and manner regulations are permissible, and a content-based prohibition must be narrowly drawn to effectuate a compelling state interest.”

The third category was nonpublic forums. “In addition to time, place, and manner regulations, the state may reserve the forum for its intended purposes, communicative or otherwise, as long as the regulation on speech is reasonable and not an effort to suppress expression merely because public officials oppose the speaker’s view,” White explained.

There are three categories of government property for purposes of access for expressive activities: traditional public forums, limited public forums, and nonpublic forums. Two protesters carry a large banner as they walk toward a U.S. Border Patrol checkpoint on a two-lane road in Amado, Ariz., about 20 miles north of the Mexican border in 2015. The U.S. Circuit of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit said it lacked the information necessary to decide if a U.S. Border Patrol enforcement zone around a highway checkpoint in southern Arizona was a nonpublic forum as argued by the District Court in Arizona. (AP Photo/Astrid Galvan, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Government has limited ability to impose restrictions in designated public forums

In the Court’s forum-based approach, the government can impose reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on speech in all three categories of property, but has limited ability to impose content-based restrictions on traditional or designated public forums. In determining whether a government property should be classified as a designated public forum, the courts examine the government’s “policy and practice” toward the property and whether the property is conducive to expressive activity, in order to discover the government’s intent, as explained in Cornelius v. NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (1985).

In First Amendment cases, the free-speech claimant often argues that the government has discriminated against speech based on viewpoint in some type of public forum. The government sometimes will respond that the public forum doctrine is inapplicable, because the government has engaged in government speech. For example, the Supreme Court ruled in Walker v. Sons of Confederate Veterans (2015), that the state of Texas did not create a limited or designated public forum with its specialty license plate program. Instead, the specialty license plate program was a form of government speech.

In 2019, the 2nd and 4th Circuit Courts of Appeals ruled that government use of social media creates a designated public forum, and government officials can’t engage in viewpoint discrimination by blocking comments. In a widely watched case, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals in Knight First Amendment Institute v. Trump (2019), that President Trump violated the First Amendment by removing from the “interactive space” of his Twitter account several individuals who were very critical of him and his governmental policies. The appeals court agreed with a lower court that the interactive space associated with Trump’s Twitter account “@realDonaldTrump” is a designated public forum and that blocking individuals because of their political expression constitutes viewpoint discrimination.

However, the U.S. Supreme Court in April 2021 vacated the 2nd Circuit’s ruling and remanded the case with instructions to dismiss it for mootness, presumably because Trump was no longer president and Twitter had, in fact, deleted his account after the U.S. Capitol riots.

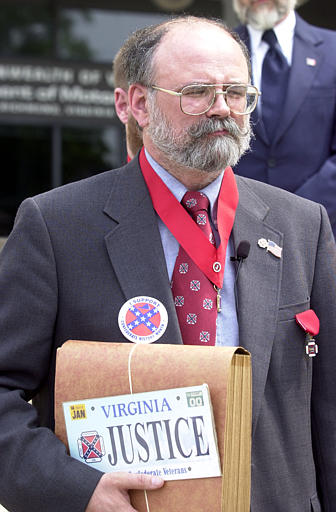

The Supreme Court ruled in Walker v. Sons of Confederate Veterans (2015), that the state of specialty license plates program was a form of government speech. In this photo, Henry E. Kidd, state commander of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, is seen during a news conference on the steps of the Commonwealth of Virginia’s Department of Motor Vehicles in Richmond, Virgina, May 2, 2002, to discuss a proposed Confederate license plate. Kidd is holding a sample plate. (AP Photo/Mark Gormus, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Public forum doctrine is ambiguous

The public forum doctrine is less than clear. Some lower courts have identified a difference between designated and limited public forums. For example, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has explained in Faith Center Church Evangelistic Ministries v. Glover (2007): “A limited public forum is a sub-category of the designated public forum, where the government opens a nonpublic forum but reserves access to it for only certain groups or categories of speech.”

Commentators have criticized the public forum doctrine and its application by the courts. For example, law professors John Nowak and Dan Farber wrote in a 1984 article: “Classification of public places as various types of forums has only confused judicial opinions by diverting attention from the real first amendment issues involved in the cases.” The doctrine nonetheless remains a staple in modern First Amendment jurisprudence.

More recently, First Amendment scholar Aaron Caplan has likened the public forum doctrine to “kudzu,” explaining that “there is not even agreement as to how many levels of forum exist within the public forum doctrine.” (Caplan 654).

Whatever its shortcomings, the public forum doctrine has a pervasive presence in First Amendment free-speech law. In the 2016-2017 term, the U.S. Supreme Court mentioned the concept of public forum in both Matal v. Tam (2017) and Packingham v. North Carolina (2017).

Updated April 2021 by Deborah Fisher. David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.