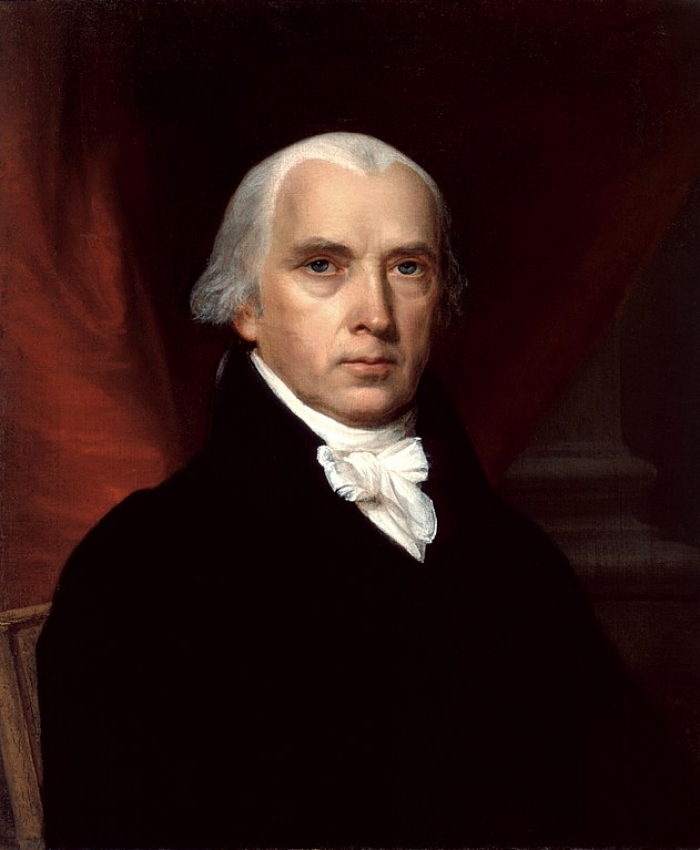

James Madison was one of the most important contributors to the Bill of Rights (1791) and later served as the fourth president of the United States. Although his role in protecting religious liberty by helping draft the Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) and sponsoring the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1779) is relatively well known, his work on the “Detached Memoranda,” written between 1817 and 1832, is less so. This document, first published in full in 1946, reveals Madison’s increasing emphasis on separation of church and state, showing that he second-guessed some of the actions that he had taken as President.

In addition to reminiscing about his experiences at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, as a coauthor of The Federalist Papers, and as a member of Congress during the Washington administration, Madison addresses church-state issues in the Memoranda.

Madison wrote ‘Detached Memoranda’ to discuss First Amendment church-state issues

In discussing the dangers of “Ecclesiastical Endowments,” Madison cites his presidential vetoes of bills that would have permitted the incorporation of religious bodies in the District of Columbia, and he recalls opposing a Kentucky measure attempting “to exempt Houses of Worship from taxes” (Fleet 1946: 555).

He reviews his role in circulating the “Memorial and Remonstrance” against religious assessment (taxes used for paying ministers to teach) in Virginia, reiterating “the danger of encroachment by Ecclesiastical Bodies” and the threat of “indefinite accumulation of property from the capacity of holding it in perpetuity by ecclesiastical corporations” (p.556).

He argues that the United States needs to learn from the example of religious conflict in Europe on this point, and he observes that Americans, who owed their independence to “the wisdom of descrying in the minute tax of 3 pence on tea, the magnitude of the evil comprised in the precedent,” need to exercise the same caution in regard to religious assessment.

Madison argued against chaplains

Next addressing the issue of congressional chaplains, Madison argues that “the establishment of the chaplainship to Congs is a palpable violation of equal rights, as well as of Constitutional principles” (p. 558).

He notes the unlikelihood that members of minority religions would ever be appointed to the post and suggests that members who want a chaplain should pay for him out of their own expenses. Madison takes a similar view of chaplaincies for the military, which he states would be better served by volunteers than by individuals paid by the government.

Acknowledging that “navies with insulated crews may be less within the scope of these reflections,” he argues that “it is safer to trust the consequences of a right principle, than reasonings in support of a bad one” (p. 560).

Madison discussed proclamations of Thanksgiving

Although Madison had himself issued proclamations of thanksgiving and fasts during his presidency, he observes that government has no legitimate authority in this area and that “an advisory Govt is a contradiction in terms” (p. 560).

When such proclamations are issued, he considers it particularly important to avoid direct mention of Jesus and to employ “a form & language” that would “deaden as much as possible any claim of political right to enjoin religious observances by resting these expressly on the voluntary compliance of individuals, and even by limiting the recommendation to such as wished simultaneous as well as voluntary performance of a religious act on the occasion.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.