Book banning, a form of censorship, occurs when private individuals, government officials, or organizations remove books from libraries, school reading lists, or bookstore shelves because they object to their content, ideas, or themes. Those advocating a ban complain typically that the book in question contains graphic violence, expresses disrespect for parents and family, is sexually explicit, exalts evil, lacks literary merit, is unsuitable for a particular age group, or includes offensive language.

Book banning is the most widespread form of censorship in the U.S.

Book banning is the most widespread form of censorship in the United States, with children’s literature being the primary target. Advocates for banning a book or certain books fear that children will be swayed by its contents, which they regard as potentially dangerous. They commonly fear that these publications will present ideas, raise questions, and incite critical inquiry among children that parents, political groups, or religious organizations are not ready to address or that they find inappropriate.

Most challenges and bans prior to the 1970s focused primarily on obscenity and explicit sexuality. Common targets included D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterly’s Lover and James Joyce’s Ulysses. In the late 1970s, attacks were launched on ideologies expressed in books.

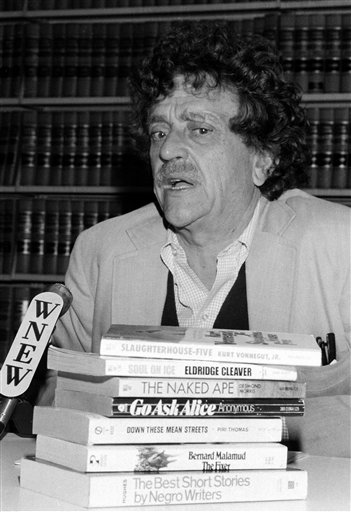

To counter charges of censorship, opponents of publications sometimes use the tactic of restricting access rather than calling for the physical removal of books. Opponents of bans argue that by restricting information and discouraging freedom of thought, censors undermine one of the primary functions of education: teaching students how to think for themselves. Such actions, assert free speech proponents, endanger tolerance, free expression, and democracy. In this photo, author Kurt Vonnegut Jr., speaks to reporters on a federal court ruling calling for a trial to determine if a Long Island school board can ban a number of books, including his “Slaughterhouse Five,” at New York Civil Liberty offices in 1980. (AP Photo-File, used with permission from the Associated Press)

In September 1990, the Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression declared the First Amendment to be “in perilous condition across the nation” based on the results of a comprehensive survey on free expression. Even literary classics, including Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, were targeted. Often, the complaints arose from individual parents or school board members. At other times, however, the pressure to censor came from such public interest groups as the Moral Majority.

Censorship — the suppression of ideas and information — can occur at any stage or level of publication, distribution, or institutional control. Some pressure groups claim that the public funding of most schools and libraries makes community censorship of their holdings legitimate.

To counter charges of censorship, opponents of publications sometimes use the tactic of restricting access rather than calling for the physical removal of books. Opponents of bans argue that by restricting information and discouraging freedom of thought, censors undermine one of the primary functions of education: teaching students how to think for themselves. Such actions, assert free speech proponents, endanger tolerance, free expression, and democracy.

Community standards may be taken into account in book banning

Although censorship violates the First Amendment right to freedom of speech, some limitations are constitutionally permissible. The courts have told public officials at all levels that they may take community standards into account when deciding whether materials are obscene or pornographic and thus subject to censor.

They cannot, however, censor publications by generally accepted authors — such as Mark Twain, for example, J. K. Rowling, R. L. Stine, Judy Blume, or Robert Cormier — in order to placate a small segment of the community. Cormier’s Chocolate War was one of the American Library Association’s Top 10 Banned Books for 2005 and 2006.

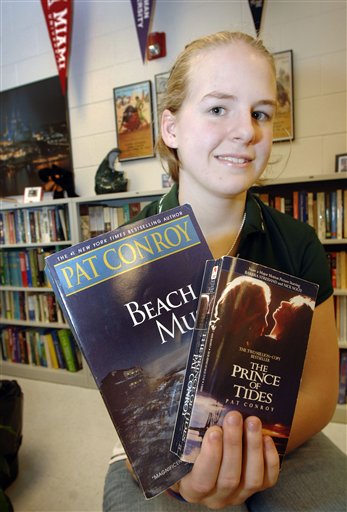

Those who oppose book banning emphasize that the First Amendment protects students’ rights to receive and express ideas. The Supreme Court in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982) ruled 5-4 that public schools can bar books that are “pervasively vulgar” or not right for the curriculum, but they cannot remove books “simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.” The Court’s decision was, however, narrow, applying only to the removal of books from school library shelves. In this photo, Makenzie Hatfield a student at George Washington high school, holds banned books by author Pat Conroy in West Virginia in 2007. The Pat Conroy books “Beach Music” and “The Prince of Tides” were suspended from nearby Nitro High School English classes after parents of two students complained about depictions of violence, suicide and sexual assault. Conroy defended the books in an e-mail reply last month to Hatfield, who teamed with classmates and Nitro students to form a coalition against censorship. (AP Photo/Jeff Gentner, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Opponents of book banning emphasize student rights

Those who oppose book banning emphasize that the First Amendment protects students’ rights to receive and express ideas. The Supreme Court in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982) ruled 5-4 that public schools can bar books that are “pervasively vulgar” or not right for the curriculum, but they cannot remove books “simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.” The Court’s decision was, however, narrow, applying only to the removal of books from school library shelves.

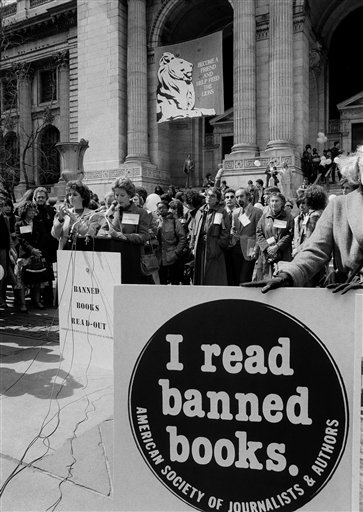

The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom documents censorship incidents around the country and suggests strategies for dealing with them. Each September, the American Library Association, the American Booksellers Association, the American Society of Journalists and Authors, the Association of American Publishers, and the National Association of College Stores sponsor Banned Books Week — Celebrating the Freedom to Read.

Designed to “emphasize that imposing information restraints on a free people is far more dangerous than any ideas that may be expressed in that information,” the week highlights banned works, encourages citizens to explore new ideas, and provides a variety of materials to promote free speech events.

The American Library Association publishes the bimonthly Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom, which provides information on censorship, as well as an annual annotated list of books and other materials that have been censored.

This article was originally published in 2009. Susan Webb is an Adjunct Librarian at Southeastern Oklahoma State University.