In Focus

Universal Screening and Reading Skill Development

Universal screening is the foundation of the Response-To-Intervention (RTI) model

of student support implemented in Tennessee in 2014. RTI was implemented in an attempt

to thwart the wait to fail model historically relied on by schools. The hope of RTI

is that schools fail to wait as students struggle to acquire basic skills. Instead,

they provide timely skills-based intervention to support struggling students. Many

school districts across the nation utilize the RTI process and universal screening.

Universal screening consists of administering developmentally and instructionally

appropriate measures to identify students who may need additional support. Universal

screening measures are typically brief measures. Many are administered as a one-minute

assessment. Measures may be administered to the whole class (e.g., Reading Comprehension

MAZE measure) or the individual (e.g., Oral Reading Fluency measure). The infographic

on p. 15 explores typical reading development milestones and aligns these milestones

to developmentally and instructionally appropriate universal screening measures.

What?

Reading comprehension is the ultimate goal of reading. Reading comprehension comprises

many different processes and relies on several foundational skills. Reading comprehension is often represented

by Scarborough’s (2001) model of reading and the associated reading rope graphic.

Reading comprehension is divided into two main strands in Scarborough’s model: word

recognition and language comprehension. The word recognition strand encompasses the

core skills of phonological awareness, sight words, and decoding. The language comprehension

strand includes background knowledge, vocabulary knowledge, language structures, verbal

reasoning, and literacy knowledge.

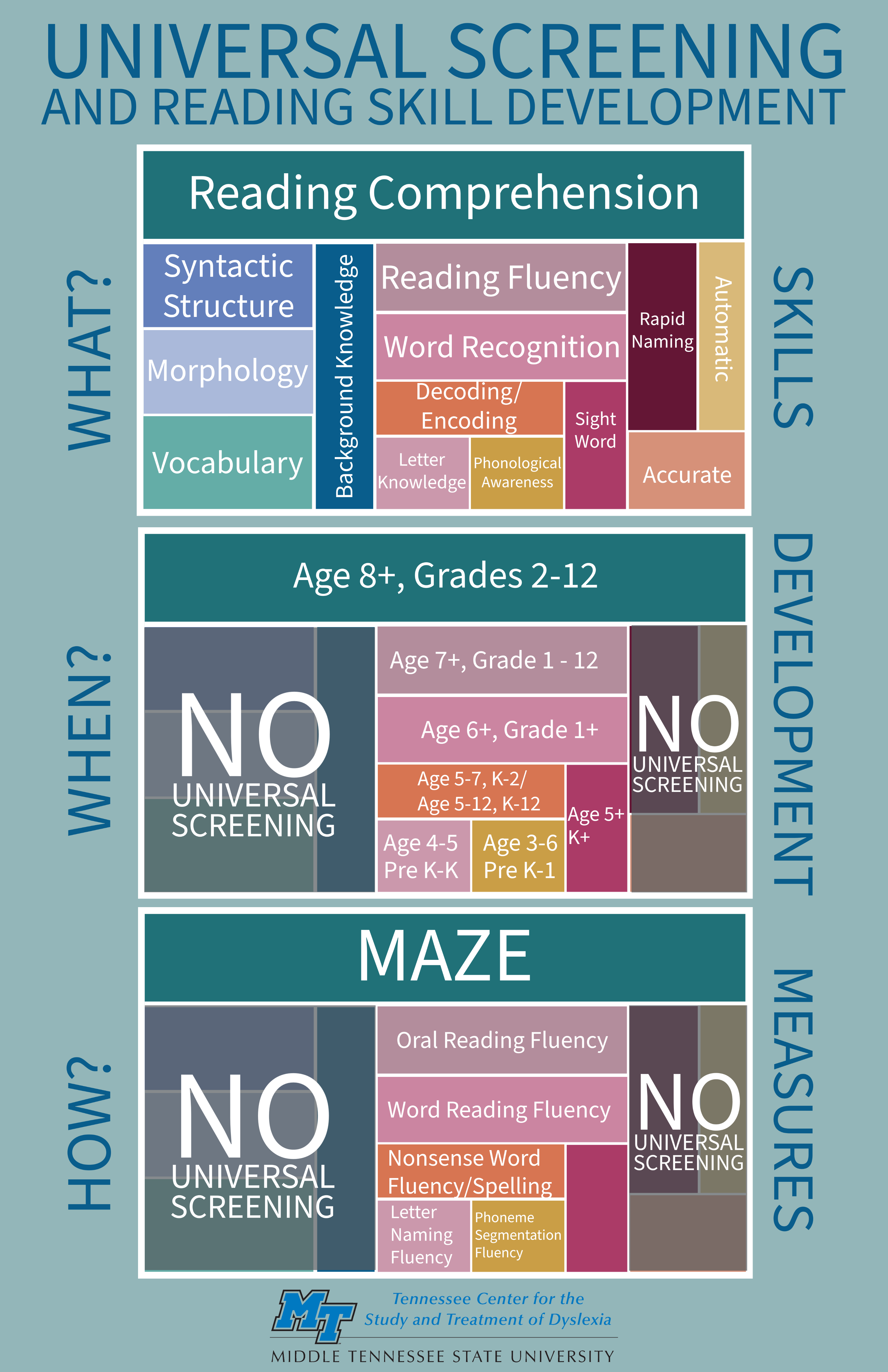

Similarly, the center’s model of reading comprehension, i.e., the reading wall, represents skills and processes that contribute to reading comprehension. The top block of the infographic represents reading comprehension and includes the skills that support reading comprehension. Each subskill supports and contributes to the efficiency and accuracy of the skills above. For example, a reader needs to know letter-sound relationships to decode new or unknown words successfully.

Phonological awareness, which includes phonemic awareness, is an essential foundational

building block to develop accurate sound-symbol representations. As sound-symbol knowledge

is consolidated and instruction in syllable types is provided, readers decode in larger

chunks, and spelling (i.e., encoding) skills develop through direct instruction and

practice. As readers consolidate this knowledge and practice these skills, fluency

is built, and readers become better able to accurately and automatically decode and

identify words in connected text.

These basic skills and processes make reading comprehension possible, but they are

insufficient in isolation. Decoding and word recognition is the first step in reading

comprehension. Readers also must have adequate background, vocabulary, and syntactic

knowledge to understand the meaning of words in context. Building basic reading skills

is the first, critical step in the process of developing reading comprehension.

When?

The middle block of the infographic presents the timeline for the development of skills

commonly tested by universal screening. Please note that all skills that support reading

comprehension are not typically included in universal screening process. The areas

that are not currently part of the universal screening process are greyed out in the

infographic. These areas are often included in more diagnostic assessments, e.g.,

screening for characteristics of dyslexia. While the terms accurate and automatic

appear greyed out in the infographic, accuracy and automaticity are essential components

included in timed universal screening measures.

Phonological awareness includes an awareness of syllable and word boundaries as well

as rhyme, alliteration, onset-rime awareness (ages 3–4), and phonemic awareness. Phonemic

awareness includes identifying, blending, segmenting, deleting, and manipulating phonemes

(ages 5–6). Weaknesses in phonological awareness, and especially phonemic awareness,

contribute to difficulty establishing sound-symbol relationships. Letter knowledge

typically develops as students receive direct instruction in the alphabet and phonics.

Depending on a child’s exposure to direct instruction, letter knowledge and sound-symbol

knowledge develop around 4–5 years old. Decoding (ages 5–7) and encoding (ages 5–12)

skills strengthen as children receive direct instruction in spelling, syllable types,

and syllable boundaries.

As readers consolidate and practice these basic skills, accuracy and automaticity

in reading connected text builds. Fluency continues to improve with practice, and

typical students begin to demonstrate efficient reading around the second semester

of first grade (ages 7+). These skills contribute to the development of reading comprehension.

Vocabulary, morphology, background, and syntactic knowledge also contribute to reading

comprehension. Reading comprehension skills develop over the course of a reader’s

life, but universal screening for reading comprehension is developmentally appropriate

beginning in the second grade when a student should have consolidated the underlying

skills (i.e., accuracy) and built automaticity for reading comprehension.

How?

There are many measures that can provide information about the development of each

of the skills. One example measure is listed in the third block of the infographic.

These are common measures available from testing companies (e.g., Pearson) or organizations

(e.g., DIBELS from the University of Oregon). Please note that this is not a comprehensive

list of measures. For example, phonemic awareness may also be measured with an initial

sound fluency measure. The age or grade should be used to determine an appropriate

measure. The instruction provided to the student should also be considered when selecting

and interpreting screening measures. A measure that serves as a universal screener

at a lower grade level may be used as a diagnostic screener for a student at a higher

grade level.

Outcome measures that represent the consolidation of basic skills (i.e., fluency and

reading comprehension) necessarily include those subskills (decoding, letter-sound

knowledge, phonological awareness). However, it is not possible to determine if a

student has a weakness in an underlying subskill based on an outcome measure. For

example, a student identified as needing additional support through universal screening

using an oral reading fluency measure cannot be presumed to have underlying weaknesses

in phonological awareness and sound-symbol knowledge. To determine the student’s strength

or weakness with these skills, a specific measure targeting only these skills should

be administered.

Universal screening is the first step in identifying potential need for intervention.

Dyslexia-specific or diagnostic screening guides intervention. For more information

on developmentally aligned universal screening measures and their appropriate use,

please see our publication Dyslexia within RTI.

|

|

Tennessee Center for the Study and Treatment of Dyslexia

615-494-8880

dyslexia@mtsu.edu

@DyslexiaMTSU

@MTSUDyslexia Center

mtsudyslexia