Recent Findings

Determining if reading problems are unexpected is hard: Concerns about the proposed

listening comprehension-reading comprehension discrepancy index

At our center, we consume, produce, use, and share research findings. We have ongoing and evolving discussions about research within our center. These discussions also extend to our various stakeholders. A recent article in the Annals of Dyslexia by Tim Odegard, Ph.D.; Emily Farris, Ph.D.; and Julie Washington, Ph.D., contributes to the conversation about the conceptualization of dyslexia.

Background motivating the study

Theoretical models about the identification of dyslexia are multifaceted. Educational policies outlining identification procedures also involve many components. The ability to identify an individual with dyslexia can be challenging. There is no single test or point of data that by itself can be used to definitively confirm an individual has dyslexia.

Closely related to identification issues are discussions of prevalence. Knowledge of how common, or prevalent, a condition is can impact decisions. Prevalence estimates influence funding and resource allocation across many settings. The prevalence estimates for dyslexia range from 5% to 17.5% of the population. Because dyslexia is common, attention and resources are expended on it. Researchers, educators, politicians, and families contribute to understanding and treating individuals with dyslexia.

|

|

Both prevalence estimates and identification decisions depend on the operational definition of dyslexia. Current definitions of dyslexia begin by describing it. The primary characteristics are difficulties with word reading, decoding, and spelling. Next, constraints are added. They are attempts to create clear boundaries. We want to be able to easily know whether someone who struggles to read well has dyslexia or if the person’s difficulties are due to other reasons. Some of these constraints lead to a search for what caused the reading problems.

Other constraints are set up to show that the individual’s difficulties are isolated to reading. Currently, reading difficulties are described as being unexpected in individuals with dyslexia. The person is described as having reading problems despite receiving effective classroom instruction. They have reading problems despite having adequate hearing and visual acuity. Lastly, their level of performance in reading is unexpected because it differs from their performance in other areas.

Researchers and practitioners continue to discuss the concept of unexpectedness. Often a search for discrepancies ensues. The search is to show that a person’s reading struggles are unexpected. Many of these efforts have been criticized. For example, there are numerous concerns about using IQ scores to demonstrate a discrepancy between a person’s achievement in reading and their intellectual ability (e.g., Siegel, 1989; 1999; Stanovich, 1991; 1999). A substantial concern is that the IQ score represents past learning, not the potential to learn.

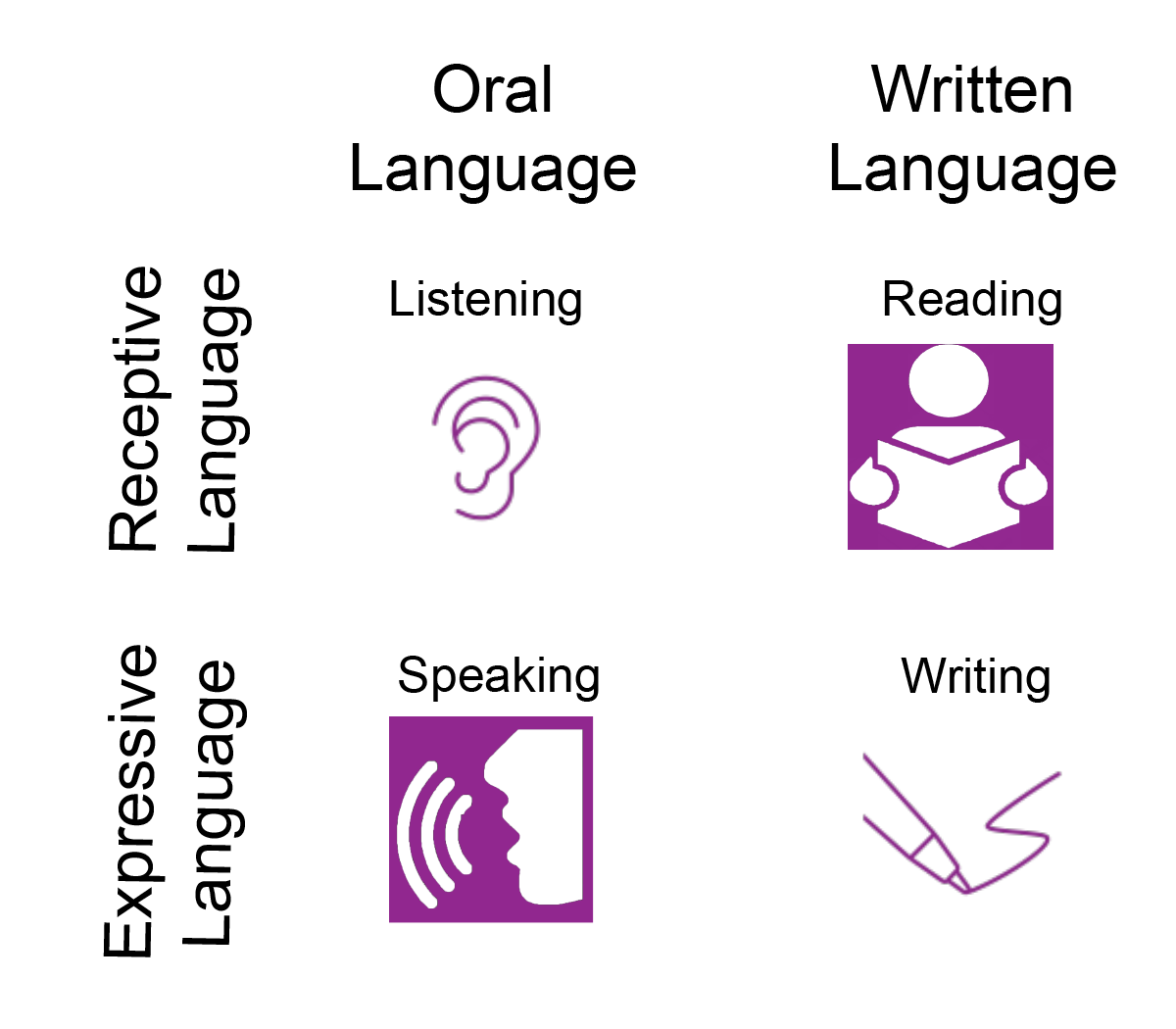

Recently, a new way to determine whether reading deficits are unexpected was proposed. It compares an individual’s listening comprehension and reading comprehension abilities. It is the LC-RC discrepancy index. Here LC refers to listening comprehension, and RC refers