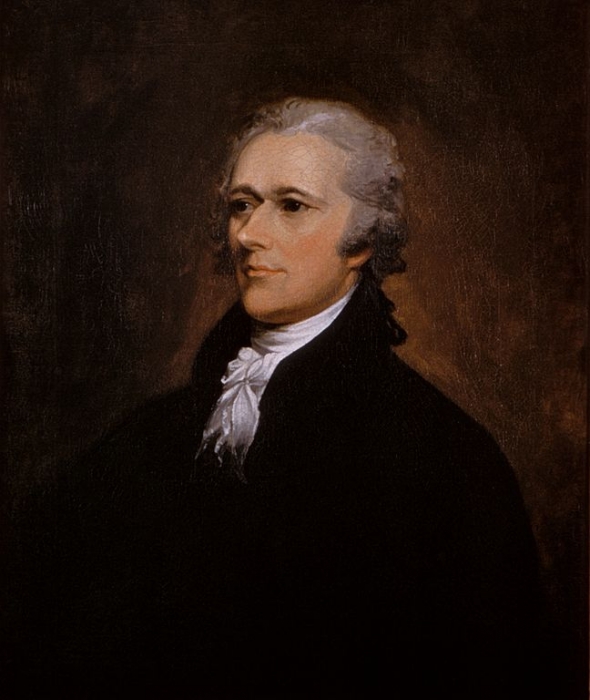

Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804), a lawyer, statesman, and founder of the Federalist Party, is remembered for his role in the formation and ratification of the Constitution, for his broad interpretations of federal power, and for the expansive economic programs (which included the establishment of a national bank) that he implemented as secretary of the Treasury under President George Washington.

Hamilton has mixed First Amendment legacy

Hamilton and James Madison were the leading contributors to The Federalist Papers, a series of articles that argued for adoption of the federal Constitution.

Hoping to forestall ratification of the new Constitution, Hamilton had used these essays to argue that a bill of rights, including protections of freedom of speech and press, was unnecessary, since the new Constitution was not vesting the federal government with power over these rights.

Hamilton’s initial opposition to adoption of the Bill of Rights and subsequent support of the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 have sometimes overshadowed his lifelong concern with the individual liberties guaranteed by the First Amendment. Although Hamilton was critical of some aspects of the Alien and Sedition laws, he supported their general principles and urged vigorous enforcement of them.

Hamilton warned against political intolerance

Born in the West Indies, Hamilton moved to the North American colonies in 1772. He studied at King’s College (now Columbia University) in New York and served as a captain in the Revolutionary War, becoming an aide to Washington.

Although he fought the British during the Revolution, after the war he defended the rights of Tories against loyalty tests and property confiscations. He warned that the modern trend toward liberty could be reversed if the United States became politically intolerant. This danger seemed remote until the French Revolution introduced novel forms of both political and religious intolerance.

Hamilton argued for defendant in seditious libel case

Political opportunism no doubt played a role in their thinking, but during the “quasi-war” with France, 1798–1800, Hamilton and other Federalists saw the military and ideological threats from the world’s only other large republic as substantial enough to require the enactment of a sedition law.

Hamilton’s most extensive discussion of seditious libel is found in People v. Croswell (N.Y. 1804), in which Hamilton appeared before the Supreme Court of New York arguing for the defendant, Harry Croswell.

Croswell had been charged with criminal libel for his role in the publication of charges that Thomas Jefferson, then vice president, had paid James Callender to print stories maligning Washington as a traitor and John Adams as a “hoary headed incendiary.” Croswell’s prosecution was part of a Republican effort to rein in Federalist critics.

Hamilton argued for truth as a libel defense

Elevating the case into one of seditious libel, Hamilton made three arguments to refute the widely held views that the common law did not admit truth as a defense and limited juries to deciding on the fact of publication.

- First, the true common law of England and New York understood liberty of the press as “the right to publish with impunity Truth with good motives for justifiable ends though reflecting on Govt. Magistracy or Individuals.”

- Second, the true common law gave juries the right to determine the facts, including the questions of truth and intent, and to apply the law in light of the facts. Hamilton argued that the alternative view arose from a line of decisions originating in the Star Chamber, “a tyrannical and polluted source.”

- Hamilton’s last argument rested on political theory rather than precedent. The right to speak the truth with good motives about public officials is essential in the American system. “It is essential to say not only that the measure is bad and deleterious, but to hold up to the people who is the author, that, in our free and elective government, he may be removed from the seat of power. If this not be done, then in vain will the voice of the people be raised against the inroads of tyranny.”

Hamilton wanted to protect public officials from libel

Hamilton did not go as far as Madison in wanting to do away with seditious libel entirely. He defined libel as a “slanderous or ridiculous writing, picture or sign, with a mischievous or malicious intent towards government, magistrates or individuals.”

Hamilton thought it necessary to protect public officials from libel so as to preserve the confidence in government necessary for its effectiveness. Furthermore, “the spirit of abuse and calumny . . . the pest of society” if unchecked would “put the best and the worst on the same level” thereby depriving voters of the ability to make an informed choice.

Hamilton’s principle of press liberty was adopted by other states

Hamilton failed to convince the court regarding the “true” common law of libel and lost the Croswell case. But his position became almost immediately the law of New York and later, in 1821, part of its constitution. The Hamiltonian principle of press liberty was adopted by some 24 other states and remained influential until the 1960s, when it was further liberalized by the Supreme Court decision in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964).

Despite his brilliant career, Hamilton’s life was cut short by a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804. Ironically, the bad blood between them stemmed in part from Hamilton’s decision to support Jefferson over Burr, when the two tied in the presidential election of 1800.

There has been renewed interest in Alexander Hamilton as a result of the Broadway production of Hamilton: An American Musical. Written by Lin-Manuel Miranda and based on the award-wining biography by Ron Chernow, the multi-racial musical highlights Hamilton’s talents and ambitions along with the tragedies of his life.

This article first published in 2009 and has been updated. The primary contributor, Peter McNamara, is a Professor in the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership at Arizona State University. It has been updated by the First Amendment Encyclopedia.