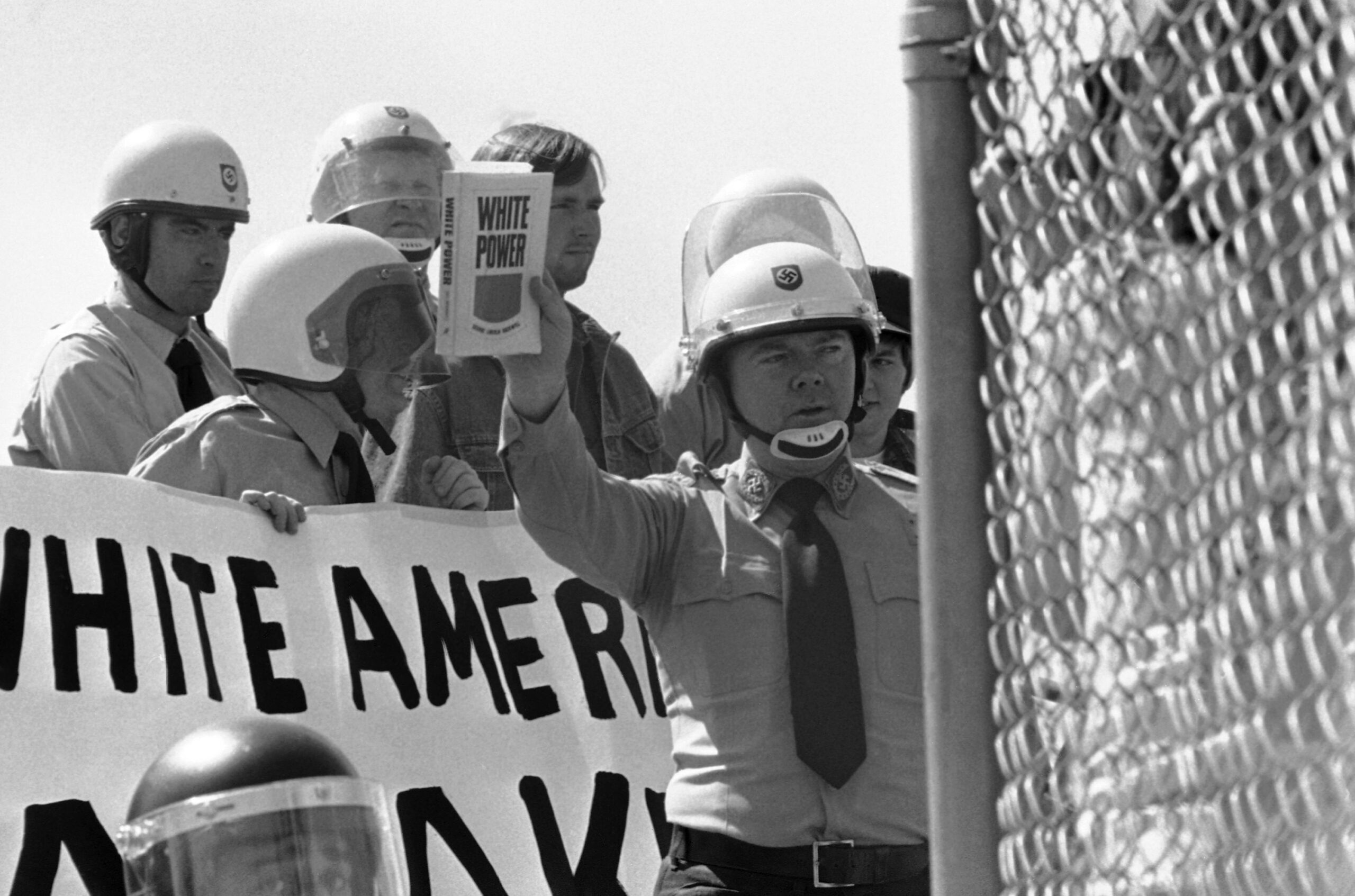

George Lincoln Rockwell founded the American Nazi Party in 1959 with the mission of killing all Jews, sending blacks to Africa, and furthering other racial policies.

The party ventured into politics in 1964, when Rockwell ran for president. Rockwell was assassinated in 1967 by John Patler, a former member of Rockwell’s group, but the party’s legacy continued, leading to the formation of several offshoots.

One of those offshoots became embroiled in a controversy in 1977 and 1978 over whether it could obtain a permit to conduct a march through Skokie, Illinois, a Chicago suburb with a large Jewish population, including Holocaust survivors.

The town attempted to prevent the march, citing a city ordinance, but, eventually, in Collin v. Smith (7th Cir. 1978), the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the Skokie ordinance that made it a crime to disseminate material that might incite racial or religious violence or hatred.

Skokie officials had wanted to apply this law to the party’s display of swastikas, which would allow authorities to deny a permit for the march.

The appeals court noted that although the swastika might be an offensive symbol, its display during a peaceful march could not be considered a crime. The court wrote in its opinion that it is “the fact that our constitutional system protects minorities unpopular at a particular time or place from government harassment and intimidation, that distinguishes life in this country from life under the Third Reich.” As a result of the court’s decision, Skokie officials could not stop the march (which the party ultimately held in Chicago).

Ku Klux Klan speech has led to First Amendment doctrine

Almost ten years earlier, in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), the Supreme Court had ruled that attempts to restrict the hateful speech of Ku Klux Klan leader Clarence Brandenburg on the basis of content and subject matter violated the First Amendment.

In Brandenburg, the speech at issue was vehemently racist and anti-Semitic. Nonetheless, the Court held that speech cannot be banned solely because of its content; it could only be limited in cases where it presented the threat of imminent lawless action. Thus, when words turn to violence or intimidation, First Amendment protection becomes more limited. Take, for example, the issue of cross burning in Virginia v. Black (2003).

After a lengthy discussion of the history of the Ku Klux Klan and white supremacy, the Supreme Court’s opinion held that it is constitutional for a state to criminalize cross burning when such burning is done with the intent to intimidate, but not when it is used to make a political statement or as part of a group assembly.

These cases illustrate that the First Amendment applies to all groups so long as their intent is not to intimidate or incite violence. This is sometimes a fine line. As a result of First Amendment protections, people are often forced to tolerate speech they find offensive.

This article was originally pubished in 2009. Jason Abel is a Partner at Steptoe & Johnson LLP and leads the Campaign Finance and Political Law Practice and advises clients on a range of government affairs issues, including legislative strategy and process. Jason is a lecturer in law at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, where he teaches election law, and a professorial lecturer in law at George Washington University Law School, where he teaches campaign finance law and Congressional procedure.