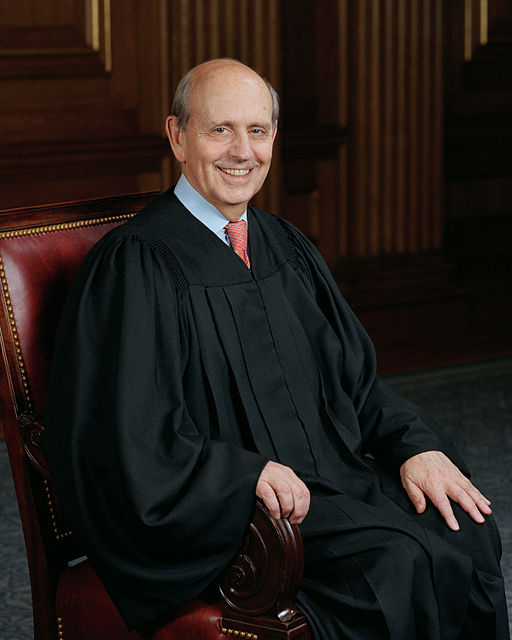

Stephen G. Breyer (1938– ) took his seat on the Supreme Court bench in 1994, replacing retired justice Harry A. Blackmun. Appointed by President Bill Clinton, he is generally regarded as a moderate liberal who decides cases pragmatically rather than on the basis of rigid ideology. His First Amendment jurisprudence reflects this approach, often making his votes more difficult to predict than those of fellow justices.

In January 2022, Breyer, at age 83, announced he would be leaving the court at the end of the current term.

Breyer wrote a draft of a First Amendment opinion as a law clerk

Born in San Francisco in 1938, Breyer was educated at Stanford University, Oxford University, and Harvard Law School; he later taught administrative law at Harvard as well. As a law clerk, Breyer wrote the first draft of Justice Arthur J. Goldberg’s concurring opinion on the right to privacy in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965). From 1965 to 1967, Breyer was a special assistant to Assistant Attorney General Donald F. Turner in the Justice Department, where he developed his expertise in anti-trust law. He then worked as an assistant special prosecutor during the Watergate investigations. Breyer served as a judge on the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals from 1981 to 1990 and was a member of the United States Sentencing Commission from 1985 to 1989.

Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer speaks to a group of writers at Fenway Park in Boston in 2006 during “The Great Fenway Park Writers Series”. Breyer has been involved in many First Amendment cases. He was the determinative vote in two Supreme Court cases involving the display of the Ten Commandments. In Van Orden v. Perry (2005), he voted to uphold a long-standing display of the commandments in a public park, and in McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union (2005), he voted against the display of two plaques in county courthouses. (AP Photo/Winslow Townson)

Breyer has been involved in many First Amendment cases

Breyer was the determinative vote in two Supreme Court cases involving the display of the Ten Commandments. In Van Orden v. Perry (2005), he voted to uphold a long-standing display of the commandments in a public park, and in McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union (2005), he voted against the display of two plaques in county courthouses.

Breyer authored the court’s majority opinion in Beard v. Banks (2006), upholding prison officials’ broad restrictions on inmates’ reading materials. He also authored the court’s main opinion in Denver Area Educational Telecommunications Consortium v. Federal Communications Commission (1996), which upheld two provisions and struck down another related to the regulation of indecent programming on cable television.

Breyer concurred with the court’s ruling in Bartnicki v. Vopper (2001) that prevented criminal liability from being imposed on those who published illegally intercepted wire communications. He stirred concern among some First Amendment experts, however, when he stated in his concurrence that ”the Constitution permits legislatures to respond flexibly to the challenges future technology may pose to the individual’s interest in basic personal privacy.”

In Morse v. Frederick (2007), he sided with the majority in supporting a principal’s right to suspend a student for holding up a banner tied to drug use, but he would have done so on the basis of the principal’s immunity from liability rather than on the basis of the First Amendment.

Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, center, reads a book to visiting fourth-grade students at the Supreme Court Library in 2007. Breyer has written dissents in First Amendment cases. He dissented in the Court’s upholding of the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 in Eldred v. Ashcroft (2003), emphasizing that the copyright clause must be read consistently with the First Amendment. (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

Breyer has authored dissents in First Amendment cases

He dissented in the court’s upholding of the Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 in Eldred v. Ashcroft (2003), emphasizing that the copyright clause must be read consistently with the First Amendment: “The Copyright Clause and the First Amendment seek related objectives — the creation and dissemination of information. When working in tandem, these provisions mutually reinforce each other. . . .At the same time, a particular statute that exceeds proper Copyright Clause bounds may set Clause and Amendment at cross-purposes, thereby depriving the public of the speech-related benefits that the Founders, through both, have promised.”

Justice Breyer joined Justice Stevens’ dissent in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), thus siding with what they considered to be the free speech of individuals over that of corporations. He took a similar stance in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission (2014). Breyer authored his own dissent in Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (2010), reading a summation of his opinion from the bench expressing his view that the individuals involved in providing aid were attempting to use peaceful means to bring about change.

He issued the lone dissent in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association (2011), which, along with other opinions, showed special concern about the need to shield minors from pornography. Breyer authored the court’s decision in Walker v. Texas Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans (2015), which upheld the right of Texas to refuse to issue license plates with pictures of the Confederate flag.

Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer testifies on Capitol Hill in 2009 before the House Financial Services and General Government subcommittee hearing on the court’s Fiscal Year 2010 appropriations. Breyer is less supportive of commercial speech and of corporate campaign contributions than most of his colleagues. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

Analysis of Breyer’s free speech jurisprudence

Benjamin Pomerance has undertaken an extensive analysis of 27 cases in which Justice Breyer has participated involving freedom of speech. Although he confirms that Breyer’s view of the First Amendment is elastic, he observes that the First Amendment is of major concern to him. Breyer has thus authored signed opinions in 21 of these cases, 11 of which were dissents, eight of which were concurring opinions, and only three of which were majority or controlling opinions (2016, pp. 476-477).

Pomerance found that Breyer’s concurring opinions often advocate a narrower reading of free speech rights than opinions by his colleagues. Breyer is far less likely to require that the court apply strict scrutiny in such circumstances, in part because he appears to have greater faith in the motives of those who govern and in part because he believes that the laws should reflect popular sentiment. Breyer is less supportive of commercial speech and of corporate campaign contributions than most of his colleagues.

Professor Eugene Volokh ranked Breyer in last place among the justices with regard to how often he issued pro–First Amendment opinions in free speech cases from 1994 to 2002.

Breyer wrote Active Liberty (first published in 2006) to explain his judicial philosophy of interpreting the Constitution, including criticism of originalist, or textualist, methods as a primary method for approaching difficult constitutional questions. In the book, he encourages citizens to increase their understanding of the Constitution. In 2010 he published Making Our Democracy Work, and in 2015 he published The Court and the World. With the death of Antonin Scalia, Breyer became the fourth-longest-serving justice on the current court.

Breyer’s First Amendment opinions in his last five years

In his last five years on the court, Breyer added opinions to a number of prominent First Amendment cases. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017), Breyer authored a concurring opinion in the decision ruling that a church child learning center had been improperly excluded from aid because it was religious in nature. In Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue (2020), he authored a dissent that expressed the view that Montana had gone too far in requiring the use of a state scholarship fund for students in private parochial schools. In Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2018), he joined a concurring opinion by Justice Kagan agreeing that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had demonstrated hostility toward a cake maker who had refused to bake a cake for a gay couple on the basis of his religious beliefs.

In National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v. Becerra (2018), Breyer authored the dissent that would have upheld disclosure requirements for clinics serving pregnant women on the basis that the information amounted to appropriate consumer protection legislation. In Agency for International Development v. Alliance for Open Society International, Inc., II (2020), Breyer authored another dissent that would have granted standing to foreign groups that were questioning a law requiring that they have a specific policy opposing “prostitution and sex trafficking.” And in Little Sisters of the Poor Saints Peter and Paul, Home v. Pennsylvania (2020) he joined Kagan’s concurring opinion in believing that the rules regarding contraception that the government had applied to the Little Sisters of the Poor were overly broad.

In Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo (2020), Breyer issued a dissent to an opinion striking down a New York order limiting church gatherings on the basis that he thought they were similar to those applied to other public meetings. He joined a similar dissent in the case of Tandon v. Newsom (2021).

Breyer, 83, announces retirement from court in 2022

At 83, Justice Breyer was, in 2022, the oldest member of the court when announced that he would be leaving that body at the end of the session, usually in late June. Although some Democrats had encouraged him to resign even earlier, he considered the decision to be very personal and disliked the idea that such decisions should be calculated in a political fashion.

Breyer’s resignation has created the opportunity for President Joe Biden to make his first appointment to that court, to which President Donald Trump had appointed three justices. Biden has promised to nominate a black woman, who if confirmed would be the first black woman and raise the number of female justices from three to four. Democrats, who have 50 seats in the Senate, which is responsible for confirmations, promised to act swiftly on any nomination he made, with obvious concern that should Republicans gain seats in the 2022 senatorial elections, they might try to delay the nomination, as they did in the last year of the Obama Administration, until after the next presidential election.

Biden seems likely to nominate a liberal Democrat to the court, and she might be somewhat to the left of Breyer but would be unlikely to tilt the court significantly from its current ideological makeup.

This article first was published in 2009 and has been updated. The primary contributor was John Vile, a professor at Middle Tennessee State University. It has been updated by other First Amendment Encyclopedia contributors.