The second woman to serve on the Supreme Court, Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1933– 2020) has consistently interpreted the establishment clause of the First Amendment to provide for a high degree of separation of church and state. She has also been a steadfast opponent of gender bias throughout her career.

Gender bias defined Ginsburg’s early career

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Ginsburg graduated from Cornell University in 1954. In 1959 she earned a law degree from Columbia University, where she finished first in her class. One of her professors recommended her for a clerkship with Justice Felix Frankfurter, who said he was not ready to hire a female law clerk. When gender bias denied her a professional job in private law practice, Ginsburg carved out a distinguished career as a law professor, first teaching at Rutgers University, from 1963 to 1972, and then at Columbia until 1980. During this time, she worked for the American Civil Liberties Union, arguing many gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court.

In 1980 President Jimmy Carter nominated her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, where she served until 1993, when President Bill Clinton nominated her to the Supreme Court. The Senate confirmed her by a vote of 96-3.

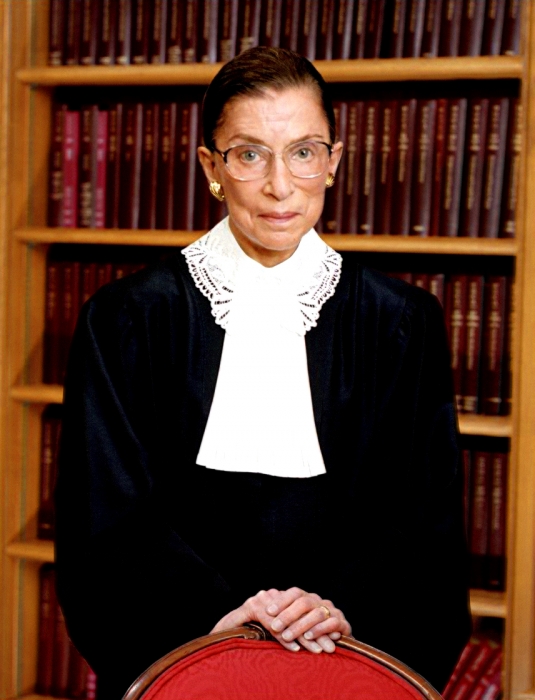

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg addresses reporters in the Rose Garden of the White House in 1993 in Washington after President Bill Clinton said he would nominate her for the Supreme Court. Ginsburg has been a steadfast opponent of gender bias throughout her career, arguing many gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court during her time at the American Civil Liberties Union. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Ginsburg has written several majority opinions in First Amendment cases

Ginsburg has written several majority opinions in First Amendment cases. Among them are Wood v. Moss (2014), a case granting qualified immunity to Secret Service agents who allegedly treated anti-President protestors worse than those cheering for the President; Golan v. Holder (2012), a case rejecting a First Amendment challenge to a copyright law; Christian Legal Society Chapter of the Univ. of Calif. v. Martinez (2010), a decision upholding a university’s policy against discrimination even as applied to student religious groups; Illinois ex rel. Madigan v. Telemarketing Associates, Inc. (2003), a decision about charitable solicitations; Eldred v. Ashcroft (2003), a ruling that extended copyright protection; Buckley v. American Constitutional Law Foundation (1999), a political speech case; and Ibanez v. Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation (1994), a commercial speech decision.

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg testifies before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1993. Ginsburg has written several majority opinions in First Amendment cases, while also frequently voting in a First Amendment–friendly manner in dissent. (AP Photo/John Duricka, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Ginsburg has also upheld the First Amendment through dissent

Ginsburg has frequently voted in a First Amendment–friendly manner in dissent. She authored a dissenting opinion in FCC v. Fox (2009), showing her doubt as to the validity of the Court’s decision in the broadcast indecency case FCC v. Pacifica Foundation (1978). She and Justice John Paul Stevens were the only dissenters in Beard v. Banks (2006), where the Court majority rejected a prisoner’s claim that the prison’s ban on reading material violated the First Amendment. She also dissented in City of Erie v. Pap’s A.M. (2000), which ruled that an ordinance against nude dancing did not violate the principle of free expression. Ginsburg generally has been a strong defender of commercial speech. For example, she joined Justice Anthony M. Kennedy’s potent dissent in an attorney advertising decision, Florida Bar v. Went for It, Inc. (1995).

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg takes part in a swearing-in ceremony at the State Department in Washington in 2005. Ginsburg’s commitment to the separation of church and state is shown in cases such as Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), when the majority upheld an Ohio school voucher law that provided tuition assistance for religious and nonreligious schools, and in Van Orden v. Perry (2005), when the majority upheld the constitutionality of a display of the Ten Commandments in a public park in Austin, Texas. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Ginsburg dissented from the majority opinion in Capitol Square Review and Advisory Board v. Pinette (1995), reversing a decision that had denied the Ku Klux Klan a permit to leave an unattended cross on the statehouse square in Columbus, Ohio. She wrote, “No human speaker was present to disassociate the religious symbol from the State. No other private display was in sight. No plainly visible sign informed the public that the cross belonged to the Klan and that Ohio’s government did not endorse the display’s message.”

She dissented from the Court’s decision in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), when the majority upheld an Ohio school voucher law that provided tuition assistance for religious and nonreligious schools, and in Van Orden v. Perry (2005), when the majority upheld the constitutionality of a display of the Ten Commandments in a public park in Austin, Texas. In each of these cases, which featured multiple decisions, Ginsburg chose not to write separately.

Ginsburg died on September 18, 2020, at age 87.

This article first was published in 2009 and has been updated. The primary contributor was David L. Hudson, a professor at Belmont. It has been updated by other First Amendment Encyclopedia contributors.