Thurgood Marshall (1908–1993), the first African-American to serve on the Supreme Court, consistently championed First Amendment and other individual rights. He viewed the amended Constitution, in the words of his biographer Juan Williams, as “essentially a manifesto of individual liberty” (p. 400).

Marshall aruged Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court

Marshall was born in Baltimore, Maryland. He earned an undergraduate degree from Lincoln University in 1930 and a law degree from Howard University Law School in 1933. At Howard, where he was first in his class, he was mentored by Charles Houston, a professor and leader of the NAACP (the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). Marshall later became chief counsel for the NAACP and argued numerous civil rights cases before the Supreme Court. Most significant was Brown v. Board of Education (1954), a landmark case that provided for racial desegregation of public schools.

President John F. Kennedy appointed Marshall to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed him to the position of solicitor general. Two years later, Johnson nominated him to the Supreme Court. He was confirmed by the Senate in 1967.

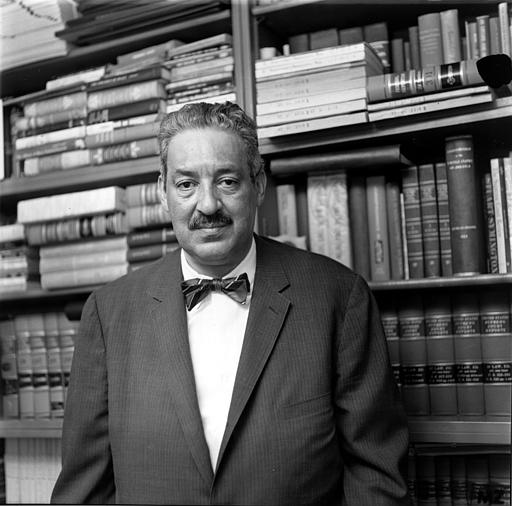

Thurgood Marshall in his New York residence in 1962 after the Senate confirmation of his nomination to the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Marshall was chief counsel for the NAACP and argued numerous civil rights cases before the Supreme Court. Most significant was Brown v. Board of Education (1954), a landmark case that provided for racial desegregation of public schools. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Marshall voted to protect the free speech rights of employees

On the Court, Marshall displayed great sensitivity to First Amendment freedoms and regularly voted to protect the free speech rights of employees. He wrote the Court’s seminal decision on free speech rights of public employees, Pickering v. Board of Education (1968). In that case he ruled that public school officials violated the First Amendment rights of an Illinois teacher, Marvin Pickering, when they terminated him for writing a letter criticizing school board policies to the editor of a local newspaper. Marshall, in his opinion for the Court, wrote, “The problem in any case is to arrive at a balance between the interests of the teacher, as a citizen, in commenting upon matters of public concern and the interest of the State, as an employer, in promoting the efficiency of the public services it performs through its employees.”

He also wrote the Court’s majority opinion in Rankin v. McPherson (1987), in which the Court ruled, 5-4, that a Texas constable violated the First Amendment rights of a clerical employee for making an intemperate remark about President Ronald Reagan after John Hinckley Jr. shot and wounded the president. Marshall wrote, “Vigilance is necessary to ensure that public employers do not use authority over employees to silence discourse, not because it hampers public functions but simply because superiors disagree with the content of employees’ speech.”

Marshall introduced the content discrimination principle

Marshall’s powerful language in Police Department of Chicago v. Mosley (1972) ushered in the Court’s content discrimination principle, which became the Court’s chief methodological tool for deciding free expression cases. The content discrimination principle determined whether a regulation discriminated against speech because of the content of its message. In Mosley, which dealt with a city law that targeted labor picketing near local schools, Marshall wrote, “But, above all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content.”

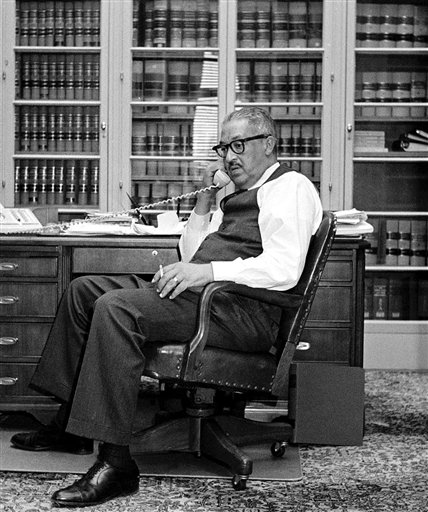

Thurgood Marshall, new solicitor general of the United States, talks on the phone in his Department of Justice office in 1965. Marshall, grandson of a slave, gave up a lifetime tenure as a Court of Appeals judge to become the government’s chief advocate before the Supreme Court. Marshall later served on the Supreme Court. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Marshall sided with public school students

Marshall also consistently sided with public school students in First Amendment cases. He joined the majority of the Court in the landmark student-speech decision, Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Comm. Sch. Dist. (1969). While Marshall did not write the Court’s opinion in Tinker, he made his presence felt at oral argument with his incisive questioning of the school board’s attorney. At oral argument, Marshall questioned whether the student’s wearing of the armbands really caused a disruption. He asked how many students wore the armbands. Upon receiving the answer of seven, Marshall asked: “Seven out of eighteen thousand, and the school board was afraid that seven students wearing armbands would disrupt eighteen thousand. Am I correct?” He later dissented when his colleagues voted against student free-speech litigants in both Bethel Sch. Dist. v. Fraser (1986) and Hazelwood Sch. Dist. v. Kuhlmeier (1988).

Marshall also voted to protect the First Amendment rights of prisoners

Marshall’s commitment to the First Amendment extended to prison inmates. In his concurring opinion in Procunier v. Martinez (1974), a case examining the constitutionality of California’s prison mail regulations, Marshall emphasized the importance of freedom of expression to the human spirit: “The First Amendment serves not only the needs of the polity but also those of the human spirit — a spirit that demands self-expression. . . . To suppress expression is to reject the basic human desire for recognition and affront the individual’s worth and dignity.”

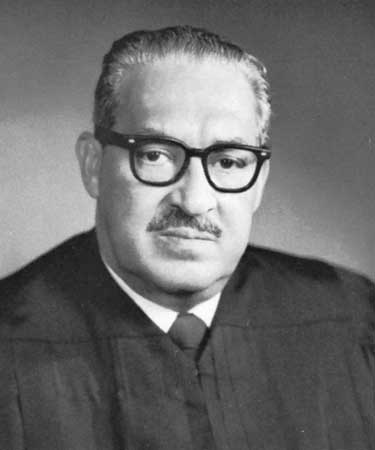

Justice Thurgood Marshall on his first day in court in 1967. Marshall advocated for the First Amendment rights of many groups, including prisoners, public employees, students, and the press. He also ruled in a controversial opnion that the government could not criminalize the private possession of obscenity. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Marshall had a controversial First Amendment opinion about obscenity

One of Marshall’s most controversial First Amendment opinions was Stanley v. Georgia (1969), which ruled that the government could not criminalize the private possession of obscenity. “If the First Amendment means anything, it means that a State has no business telling a man, sitting alone in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch,” Marshall wrote. “Our whole constitutional heritage rebels at the thought of giving government the power to control men’s minds.”

Marshall advocated for press freedom

Marshall also was a staunch advocate of freedom of the press. He wrote the Court’s opinion in Arkansas Writers’ Project, Inc. v. Ragland (1987), which invalidated a state law taxing general-interest magazines but not newspapers and professional trade journals. He noted that “the basis on which Arkansas differentiates between magazines is particularly repugnant to First Amendment principles: a magazine’s tax status depends entirely on its content.” In Florida Star v. B.J.F. (1989), he ruled that the First Amendment prohibited the state from imposing damages on a newspaper for reporting a rape victim’s name it had lawfully obtained in its police reports section.

Marshall’s was a consistent liberal voice on a Court that was increasingly conservative. He retired from the Court in 1991 and was replaced by the much more conservative Justice Clarence Thomas.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.