In a leadership manner akin to that of his political hero Abraham Lincoln, Earl Warren (1891–1974) transformed the nation as the 14th chief justice of the United States. Both Lincoln and Warren were Republicans who believed in promoting democratic values. Warren implemented the Great Emancipator’s belief in equality, fairness, and individual dignity through a human rights due-process revolution, fair-trial procedures, and fairer representation in state legislatures.

Warren was a Westerner and lifelong Republican

Born in Los Angeles, Warren was raised in the frontier town of Bakersfield, California. Warren skipped two grades in elementary school, which led to his being somewhat of an outsider in high school. After graduating in 1908, he moved to Berkeley to attend the University of California — the first youth from East Bakersfield to do so.

Determined to become a lawyer like Lincoln, Warren majored in political science at Berkeley while at the same time becoming involved in Theodore Roosevelt’s progressive politics. After three years he entered the university’s Department of Jurisprudence, ultimately receiving a Bachelor of Law degree in 1914, the same year he was admitted to the California bar.

He then began practicing law in San Francisco, becoming a lifelong Republican after the newly formed Lincoln-Roosevelt League swept progressive Hiram W. Johnson into the governorship in 1910 on an anti-railroad, reform platform. During World War I, Warren briefly served in the Army but remained stateside, rising to the rank of captain.

In 1926 Warren began his long career as an elected official as the district attorney for Alameda County. He made a name for himself fighting political corruption, and in 1938 he ran for attorney general. During that campaign, Warren’s father was murdered on May 14, 1938. After he learned that the police had found a suspect, Warren refused to let them coerce a confession, and the murder was never solved.

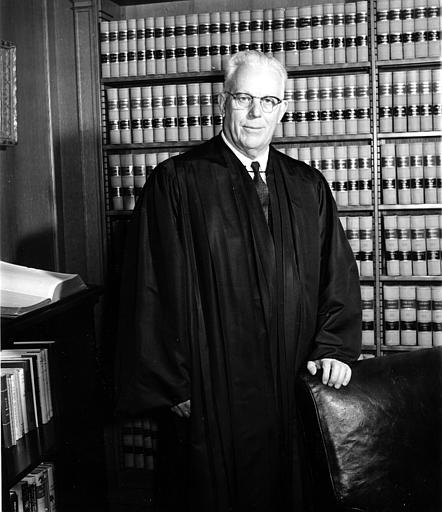

Earl Warren as a US Army Officer in 1918. Warren went on to be a popular Republican politician and chief justice of the Supreme Court. Warren’s political hero was Abraham Lincoln, and like Lincoln, Warren transformed the nation by instituting a human rights revolution through due process and more equality. (Public domain)

Warren supported Japanese internment but regretted it

He became the state’s chief law enforcement officer on Dec. 29, 1938. In that position he was swept up in the war hysteria after the attack on Pearl Harbor. As a result, he strongly supported the military’s forced evacuation of persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast even though two-thirds of them were native-born American citizens. This popular action in the state was backed by the president, Congress, and the Supreme Court. As governor and chief justice he strove to compensate for this injustice, and in his memoirs he would express belated regret over his action.

Warren was a popular politician who ran for the Republican presidential nomination

By now the most popular politician in the state, he won the governorship in 1942. Franklin D. Roosevelt refused to campaign against him; Warren garnered 57% of the vote, and his fellow Republicans won control of both chambers of the state legislature. As governor he served an unprecedented three terms, compiling a progressive record. In 1944 he twice turned down Thomas E. Dewey’s offer to serve as his running mate on the Republican ticket for president, but he did agree to join the ticket in 1948.

As a result of his vice presidential race in 1948, Warren became a contender for the 1952 Republican presidential nomination. After the contest narrowed to one between conservative Robert A. Taft and World War II hero Dwight Eisenhower, Warren threw his support behind the more moderate Eisenhower.

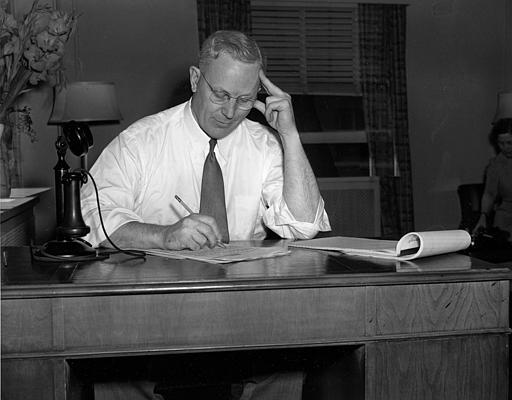

Earl Warren was the only governor of California to serve three consecutive terms. His status as a Westerner made him a sort of outsider on the Supreme Court. As an outsider, he often led his Court in serving justice for the underdogs of society, oftentimes in First Amendment issues. His personal standard for deciding cases was, “But is it fair?” In this photo, Warren, governor of California at the time, works on his keynote speech for the opening of the Republican National Convention, in Chicago,1944. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Warren was the first outsider to lead the Supreme Court

After his victory, Eisenhower promised to make Warren his first appointment to the Supreme Court. When Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson died suddenly of a heart attack on Sept. 8, 1953, Eisenhower was at first reluctant to name Warren to head the Court, but he followed through on his promise and nominated him to the chief justiceship. Warren was confirmed by the Senate on March 1, 1954.

For the first time in U.S. history the Supreme Court was led by an outsider, a Westerner whose leadership garnered the majority support of fellow outsiders on the Court. Though the number of justices allied with him fluctuated during his chief justiceship, he typically could count on the Court’s liberals, who were especially protective of First Amendment rights. These included the Court’s longest-serving justice, William O. Douglas, a poor minister’s son and a Westerner like Warren; Hugo L. Black, an Alabaman, who never graduated from high school; three religious minorities — the Catholic William J. Brennan Jr. and two Jews from immigrant families, Arthur J. Goldberg and Abe Fortas; and Thurgood Marshall, the first African-American on the Court.

Warren’s Court championed rights for underdogs in society

At various times during Warren’s tenure (1953–1969), the nation’s highest tribunal became a court of justice “of, by, and for” the underdogs in society. His personal standard for deciding cases was, “But is it fair?”

Warren demonstrated his leadership skills from the start. He persuaded his fellow justices to follow his lead in the unanimous Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which overturned Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), signaled the end of segregation in American society, and gave impetus to the civil rights movement and other contemporary movements for change.

He joined Justice Brennan’s Baker v. Carr (1962) opinion, which ultimately led to the one person–one vote representation and ended traditional malapportionment of rural legislators over urban populations. Warren considered this case as the most important one of his tenure.

Earl Warren smiles and waves while standing at the Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. in 1953 after arriving to become the 14th chief justice of the United States. Warren’s Court made many pro-First Amendment decisions, including restraining the definition of obscenity and recognizing a right to privacy in the Constitution. (AP Photo/Henry Griffin, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Warren’s Court had many First Amendment milestones

The Warren Court produced a number of First Amendment milestones. During the McCarthy era red scare, it restricted the use of the Smith Act of 1940 in Yates v. United States (1957) and Scales v. United States (1961). It further protected the rights of witnesses before congressional committees in Watkins v. United States (1957), a decision somewhat modified in Barenblatt v. United States (1959).

The Court also tried to restrain the definition of obscenity in Roth v. United States (1957) and indicated its willingness to supervise state courts on the subject in Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964). It expanded protections for the right of association in NAACP v. Button (1963) and established the actual malice test for libel suits by public officials in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964).

In Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), the Court overturned a criminal syndicalism statute (which attempted to suppress speech designed to overthrow the government or of industrial ownership) and ruled that the government could not suppress seditious speech that did not present the threat of imminent lawless action.

The Warren Court’s rights revolution was further extended in Engel v. Vitale (1962) when government-sponsored prayers in public schools were held unconstitutional and in Abington School District v. Schempp (1963), in which it extended this ban to devotional Bible reading. The latter decision established the first of two tests under the establishment clause that the Burger Court would further refine in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971).

Sympathetic to the rights of members of religious minorities, in Sherbert v. Verner (1963) the Court applied the compelling state interest test, when it ruled that states must extend unemployment benefits to individuals who lost their jobs because their religious beliefs kept them from working on their Sabbaths.

In Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the Court recognized that a general right to privacy, cobbled in part from the First Amendment, protected the rights of married couples to use birth control, and in Stanley v. Georgia (1969), it ruled that individuals could not be prosecuted for possessing obscenity in their own homes.

In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), the Court upheld the right of high school students to wear black armbands to school in protest of the war in Vietnam, although in United States v. O’Brien (1968), it did permit punishment of individuals who burned their draft cards in symbolic protest of the war.

Warren wrote the Court’s opinion in Sweezy v. New Hampshire (1957) that established the principle of academic freedom for college professors and the opinion in Bond v. Floyd (1966), which prohibited the Georgia legislature from expelling Julian Bond for comments criticizing the federal government.

He also authored the opinion in Gregory v. City of Chicago (1969), which reversed the disorderly conduct convictions of Dick Gregory and other protesters.

This article was originally published in 2009. William D. Pederson is American Studies Endowed Chair, Professor of Political Science, and Director of the International Lincoln Center at Louisiana State University Shreveport. A nationally recognized expert on the presidency and human rights, he has authored/edited some thirty books.