The Society of Friends, or Quakers, emerged as a Protestant denomination in England in the 1650s.

Quakers believed that each individual had an inner light. They held services in which members of the congregation spoke and participated in periods of silence. They advocated pacifism and refused to remove their hats in the presence of government officials.

Because of their beliefs, Quakers were persecuted and forbidden to worship freely. They thus became early advocates for the religious freedoms that were to be embedded in the First Amendment of the Constitution.

Quakers advocated for First Amendment religious freedom, other civil liberties

Quakers immigrated to the American colonies in part because of the persecution they faced in England. When they arrived in Massachusetts, they discovered that the Puritans, who controlled the colony, favored religious freedom for themselves while persecuting others.

Quakers eventually made their way to Rhode Island, where the government was sympathetic to religious toleration. When William Penn, a Quaker leader, founded the colony of Pennsylvania in 1682, under a grant from the king, the Quakers were able to establish a government built around the concept of freedom of religion. In 1701 Penn signed his Charter of Privileges, which gave all Pennsylvania residents certain basic rights, including freedom of worship.

The charter was the earliest prototype for the Bill of Rights.

Quaker beliefs later expanded into concern for civil liberties and civil rights beyond those guaranteed in the First Amendment. In 1673 they obtained passage of legislation protecting individual freedom of conscience in Rhode Island.

As pacifists, Quakers sought to protect rights of conscientious objectors to war

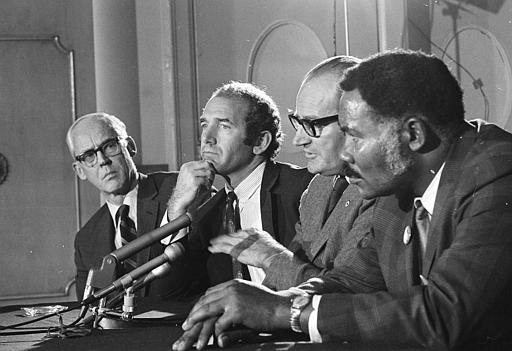

Spokesmen for a delegation of the American Friends Service Committee report on their meeting with presidential adviser Dr. Henry Kissinger in Washington in 1969. The AFSC is an international social justice organization with a mission based on Quaker philosophy. Quakers have advocated for First Amendment freedom and other civil liberties in the U.S. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Spokesmen for a delegation of the American Friends Service Committee report on their meeting with presidential adviser Dr. Henry Kissinger in Washington in 1969. The AFSC is an international social justice organization with a mission based on Quaker philosophy. Quakers have advocated for First Amendment freedom and other civil liberties in the U.S. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

By World War I, they were vigorously protecting the rights of conscientious objectors, providing legal advice through the American Friends Service Committee to those who chose to follow this path. They were also active in the abolitionist movement, the movement for woman suffrage, and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Quakers have influenced a number of landmark Supreme Court cases. In Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), Gordon Hirabayashi, a Quaker attending the University of Washington in 1942, defied the military curfew and exclusion orders that forced Japanese Americans into wartime internment camps.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled against Hirabayashi, who was acting on the Quaker belief in the freedom to be a conscientious objector.

Landmark Tinker case influenced by Quaker opposition to war

Two decades later Mary Beth Tinker and her brother John were suspended from school in Des Moines, Iowa, for wearing a black armband to protest American bombing in Vietnam. The children of a Methodist minister, they had also been influenced by Quaker opposition to war.

This time the Court ruled, in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), that the wearing of armbands was “closely akin to ‘pure speech’ ” and thus was protected by the First Amendment.

This article was originally published in 2009. J. Mark Alcorn is a high school and college history instructor in Minnesota. Hana M. Ryman is a Middle School Humanities Educator in Orlando, Florida.