In Pleasant Grove v. Summum, 555 U.S. 460 (2009), the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously determined that a city in Utah could refuse to place a permanent monument in a public park, because permanent monuments are a form of government speech immune from First Amendment review. While the decision was unanimous, there were four concurring opinions that offered different perspectives on the application of the government speech doctrine.

Religious organization tried to have a religious monument placed in a park

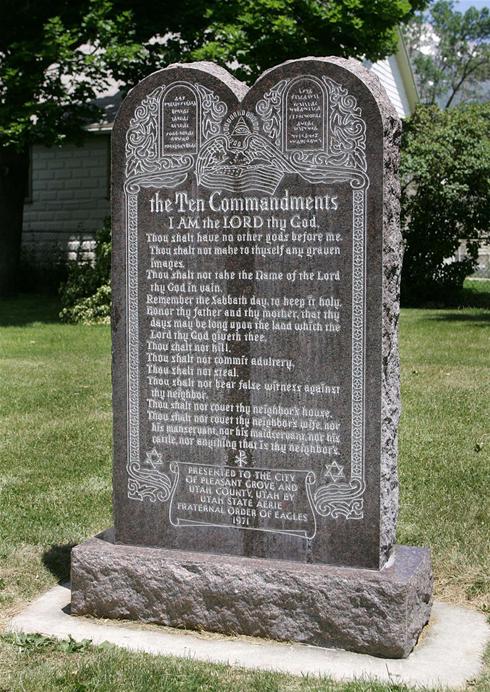

Summum, a religious organization headquartered in Salt Lake City, sought to have a monument placed in Pioneer Park in Pleasant Grove, Utah. The stone monument contained the “Seven Aphorisms of Summum” and was similar in size to a Ten Commandments monument in the park.

Lower courts said city could not deny the monument

The city denied the request, leading Summum to file a lawsuit in federal court. A federal district court ruled against Summum, but the Tenth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed. The appeals court reasoned that city officials committed viewpoint discrimination by accepting a Ten Commandments monument but rejecting the Summum monument.

Supreme Court ruled in favor of the city

On further appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Tenth Circuit and ruled in favor of the city. Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel Alito rejected the application of the public forum doctrine in this case. While a public park is a traditional public forum, Alito said that monuments in a public park were a form of government speech immune from First Amendment scrutiny.

“Permanent monuments displayed on public property typically represent government speech,” Alito wrote. “Governments have long used monuments to speak to the public.” Summum argued that the government speech rationale could be used as subterfuge for the government to engage in viewpoint discrimination. Alito recognized this as a “legitimate concern” but Alito reasoned that “public parks can accommodate only a limited number of permanent monuments.”

Justice John Paul Stevens, joined by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, wrote a concurring opinion agreeing with the result but cautioned against the expansion of the “recently minted government speech doctrine.”

Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, also wrote a concurring opinion. He stressed that the city did not violate the Establishment Clause by including a Ten Commandments monument in its park. In colorful language, he wrote: “The city ought not fear that today’s victory has propelled it from the Free Speech Clause frying pan into the Establishment Clause fire.”

Justice Stephen Breyer wrote a short concurring opinion, emphasizing that the government speech doctrine is a “rule of thumb, not a rigid category.” He warned about turning First Amendment jurisprudence into a “jurisprudence of labels.”

Justice David Souter also authored a concurring opinion, but disagreed with the idea that “public monuments are government speech categorically.” He also questioned whether the government speech doctrine would apply with traditional Establishment Clause analysis.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2017.