In Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969), the Supreme Court established that speech advocating illegal conduct is protected under the First Amendment unless the speech is likely to incite “imminent lawless action.”

The Court also made its last major statement on the application of the clear and present danger doctrine of Schenck v. United States (1919). In that case, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. had ruled that the government could punish speech if it posed “a clear and present danger of bringing about the substantive evils that Congress may prohibit.”

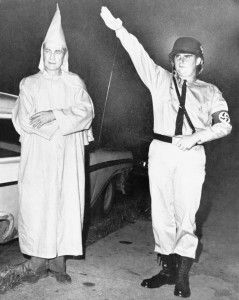

Brandenburg was convicted for his speech to Klan members

Clarence Brandenburg had addressed a small gathering of Ku Klux Klan members in a field in Hamilton County, Ohio. During the address, which was recorded by invited media representatives, Brandenburg bemoaned the fate of the “White Caucasian race” at the hands of the government.

He made anti-Semitic and anti-black statements and alluded to the possibility of “revengeance” (sic) in the event that the federal government and Court continued to “suppress the white, Caucasian race.” He also announced that the Klan members were planning to march on Washington, D.C., on Independence Day.

Brandenburg was convicted of violating Ohio’s Criminal Syndicalism law, which made it a crime to “advocate . . . the duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform.” He was fined and sentenced to serve one to 10 years in prison.

Supreme Court overturned conviction

Although the case was ultimately important in First Amendment jurisprudence, the Brandenburg matter received little attention in the Ohio court system. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and others, Brandenburg appealed to the Ohio intermediate appeal court, which upheld his conviction without opinion.

The Ohio Supreme Court declined to hear the issues, saying in its dismissal that the case presented “no substantial constitutional question.” The U.S. Supreme Court disagreed, and granted certiorari in 1968.

The Court’s unsigned, per curiam opinion was presumably drafted by Justice Abe Fortas, who had resigned by the time the final decision was handed down. The eight remaining members of the Court unanimously overturned Brandenburg’s conviction and issued a new test for all future restrictions on speech.

Court issued new ‘imminent lawless action’ speech test

Henceforth, advocacy could be punished only “where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” In so deciding, the Court specifically overruled Whitney v. California (1927), a case in which a woman had been convicted of belonging to a syndicalist organization in violation of a California law.

The Court, however, did not explicitly overrule Dennis v. United States (1951), which had upheld the convictions of Communist Party leaders even though the danger their speech posed was far from imminent.

In Dennis, the Court said that the correct interpretation of the clear and present danger doctrine allowed legislatures to decide what was dangerous; the courts in applying the clear and present danger test were simply to determine whether, on balance, the “gravity of the ‘evil,’ discounted by its improbability, justifies such invasion of free speech as is necessary to avoid the danger.” In fact, in Brandenburg, the Court cited Dennis as good law.

The Court is loath to overturn decisions it has made in recent memory, and Brandenburg was decided only 17 years after Dennis. Scholars are divided on whether Brandenburg essentially empties Dennis of any content, or merely restricts it to its particular context, that of a struggle against a large and well-organized worldwide movement.

Justice Hugo L. Black filed a brief concurrence in Brandenburg, stating his opinion that “the ‘clear and present danger’ doctrine should have no place in the interpretation of the First Amendment.” Justice William O. Douglas wrote a separate concurrence agreeing with this sentiment.

This article was originally published in 2009. James L. Walker (1942-2019) taught political science at Wright State University for 33 years.