In Bigelow v. Virginia, 421 U.S. 809 (1975), the Supreme Court established that at least some commercial advertising should receive First Amendment protection, thereby laying the groundwork for its ruling the next year in Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc. (1976), which established the modern commercial speech doctrine.

Bigelow convicted for printing abortion advertisement

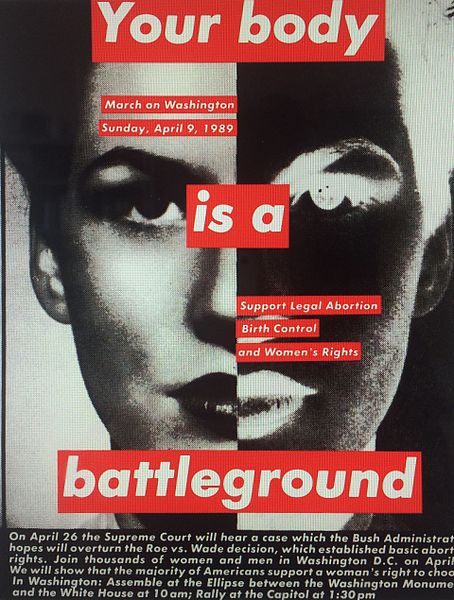

Jeffrey Cole Bigelow, managing editor of the Virginia Weekly, was convicted in Virginia for printing an abortion advertisement from a clinic in New York, where abortions were legal. Virginia law prohibited persons from encouraging or procuring abortions. The lower court that convicted Bigelow fined him $500, and his conviction was affirmed through the Virginia state court system. Initially, the U.S. Supreme Court remanded Bigelow’s case in light of its 1973 abortion decisions in Roe v. Wade and Doe v. Bolton. On remand, the Virginia Supreme Court again upheld Bigelow’s conviction, pointing out that Roe v. Wade did not mention “the subject of abortion advertising.”

Court said ad was not pure commercial speech and was protected

Bigelow again appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which granted review and invalidated his conviction by a vote of 7-2. Writing for the majority, Justice Harry A. Blackmun determined that the abortion advertisement at issue was not pure commercial speech. Had it been so, it would not have been entitled, by the precedents of the day, to any legal protection. “The advertisement in appellant’s newspaper did more than simply propose a commercial transaction,” Blackmun wrote. “It contained factual material of clear public import.”

Blackmun also noted that some advertising was entitled to a degree of First Amendment protection, though he declined to decide “the extent to which constitutional protection is afforded commercial advertising under all circumstances and in the face of all kinds of regulation.” The Virginia law, he pointed out, sought to limit what “Virginians may hear or read about New York services” — an interest, he wrote that was entitled to “little, if any, weight.” The First Amendment, according to Blackmun, prohibited the state from shielding its citizens from truthful information.

Justice William H. Rehnquist, joined by Justice Byron R. White, dissented. Rehnquist contended that the abortion advertisement was “a classic commercial proposition” not entitled to First Amendment protection.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.