The Supreme Court decision in Stanford v. Texas, 379 U.S. 476 (1965) is important for tying together First and Fourth Amendment issues. It found that, pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment, the Fourth Amendment regulations regarding using “general warrants” for search and seizure also applied to state governments, especially when items of expression, which are protected by the First Amendment, are among items to be searched or seized.

Texas authorities seized books and pamphlets from home of Communist

In December 1963, a local magistrate issued a search warrant in pursuit of any materials or documents related to the Communist Party of Texas in the private home of John William Stanford Jr.

The organization had been declared unlawful by a state law known as the Suppression Act. The search resulted in the seizure of more than 2,000 books and pamphlets; however, none of the materials were related to the Communist Party of Texas. Accordingly, Stanford filed a motion with the magistrate, requesting annulment of the warrant and the return of his property. The lower court denied Stanford’s motion with no comment. According to statute, the local court was the final decision for this matter, which left the Supreme Court as the only avenue for appeal.

The Court granted certiorari and found unanimously that the magistrate had issued a “general warrant,” or writ of assistance, which was prohibited by the Fourth Amendment.

Court said that overly broad warrants for seizing books implicated First Amendment freedoms

Most of the Court’s opinion focused on the issue of warrants and the constitutional desire to prevent the issuance of warrants that are too broad. It referenced its earlier opinion in Marcus v. Search Warrant in 1961.

Justice Potter Stewart’s opinion for the Court observed that opposition to writs of assistance has largely grown out of the “history of conflict between the Crown and the press.” He wrote, “It was in enforcing the laws licensing the publication of literature and, later, in prosecutions for seditious libel that general warrants were systematically used in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries.”

Stewart argued that it was particularly important for warrants to be specific when “the ‘things’ [to be seized] are books, and the basis for their seizure is the ideas which they contain.” He added, “No less a standard could be faithful to First Amendment freedoms.”

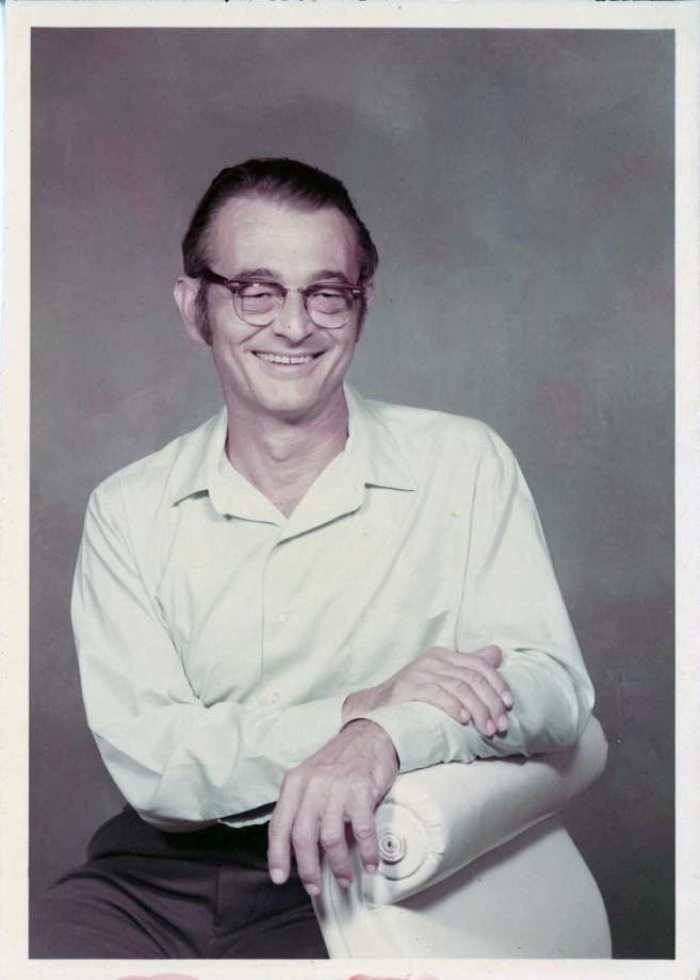

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.