Article 1, section 8, of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the right to grant copyrights and patents, which effectively give limited monopoly privileges to those who publish and invent. The issue for the Supreme Court in Bobbs-Merrill Co. v. Straus, 210 U.S. 339 (1908), was the degree to which a copyright gave an author the right to control the price of subsequent sales of a book. The Court also examined the relationship between copyrights and patents.

Publisher used copyright to say that books could not be sold for less than $1

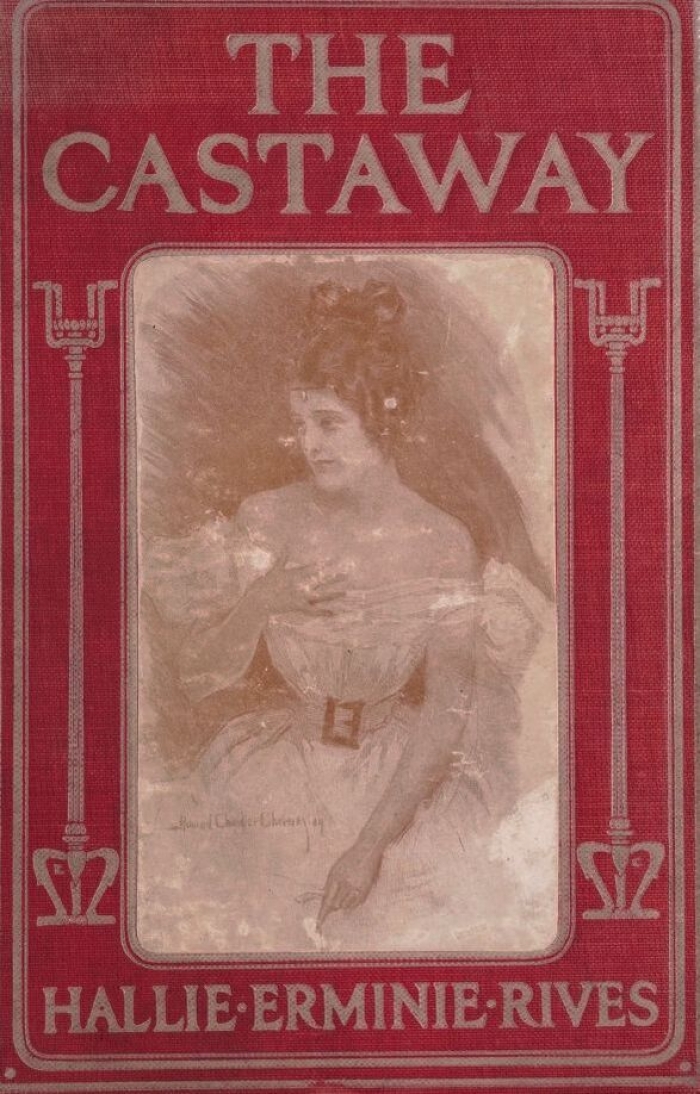

In this case, the novel The Castaway was sold by the publisher, Bobbs-Merrill, to a retailer. In publishing the book, the publisher had specified in the copyright notice that it would consider any sales of less than $1 a book to be an infringement of its copyright. Isidor and Nathan Straus, associated with R. H. Macy and Company, had purchased the novels at wholesale and then sold them for $.89 each.

Court said publishers could not set prices using copyright

Justice William R. Day wrote the Supreme Court’s unanimous opinion distinguishing patents from copyrights and indicating that the only law governing copyrights was statutory and could not be derived from common-law precedents.

A book published with statutory protection lost its common-law protection. In granting copyright holders “the sole right of vending the same,” the copyright law did not intend to allow the holder of the copyright to set the prices for which books purchased could be resold, at least not without a specific “contract limitation” or other “license agreement.”

Rather, it sought to allow an author the right “to multiply copies of his work,” and this right was not infringed by subsequent discounts.

The “first sale doctrine” was subsequently embodied in the 1909 Copyright Act. The ruling and the law that followed undoubtedly enhanced free expression by allowing booksellers to adjust prices to reflect supply and demand.

John Vile is professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.