In Laird v. Tatum, 408 U.S. 1 (1972), the Supreme Court decided to dismiss a challenge to an army surveillance program directed at civilians on the basis that the “chilling effect” on First Amendment rights the civilians were alleging was too speculative to establish legal standing.

Army surveilled civilians during Vietnam War

The army had initiated a surveillance program, which consisted mostly of gathering news clippings and some direct observation by army personnel, in order to be prepared if it were called to quell civil disturbances. This was during the period of the Vietnam War.

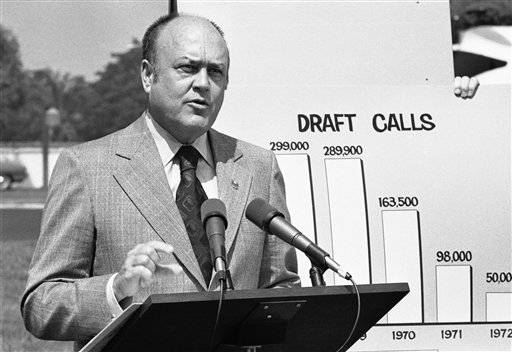

Civilians sued secretary of defense on First Amendment grounds

Although the individuals the government was watching did not point to any direct harm, they initiated a class-action suit against Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird, based on their First Amendment concerns. The district court had dismissed the case, but the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals had reversed.

Supreme Court said surveillance program did not cause actual harm

Writing for the five-person majority, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger noted that the civilians could not point to any specific actions taken against them; they could point only to the existence of an intelligence-gathering program.

Previous cases in which the Court had struck down activities that chilled freedom of expression had rested on actual “objective harm or a threat of specific future harm” that individuals experienced, rather than resting primarily on a “subjective” chill. Burger rejected the idea that the judiciary should act as a constant monitor of army surveillance activities.

Dissenters thought surveillance of citizens went too far

In a stinging dissent, Justice William O. Douglas described the army’s power to conduct civilian surveillance as “a cancer in our body politic.”

He intoned, “[S]ubmissiveness is not our heritage. The First Amendment was designed to allow rebellion. . . . The Constitution was designed to keep government off the backs of the people. The Bill of Rights was added to keep the precincts of belief and expression, of the press, of political and social activities free from surveillance.”

In a separate dissent, William J. Brennan Jr. argued that the respondents had established the basis for a justiciable case.

The case was controversial in part because Justice William H. Rehnquist refused to recuse himself, although he had been a member of the administration as head of the Office of Legal Counsel and had testified about the program to Congress before becoming a justice. This became an issue in his confirmation hearings for chief justice in 1986.

Civilians still lacked standing in similar 2013 case

Several years later in Clapper v. Amnesty International (2013), petitioners tried to argue that the government’s ability to conduct surveillance on foreign powers or agents under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) had a chilling effect on their communications with overseas contacts. But the Supreme Court ruled they lacked standing to challenge the law.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.