Associated Press v. National Labor Relations Board, 301 U.S. 103 (1937), decided the same day as National Labor Relations Board v. Jones and Laughlin Steel Corp., upheld the application of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 to the Associated Press (AP).

The Associated Press had discharged an employee for his union membership and activities.

Court said press had no immunity from labor laws

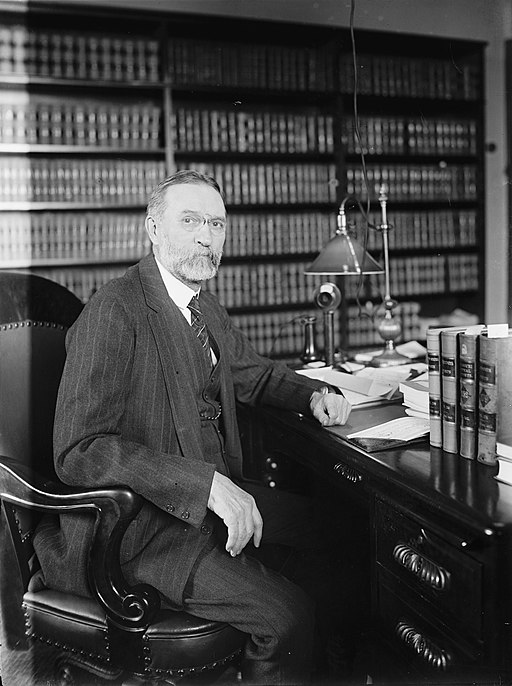

Justice Owen J. Roberts, author of the Court’s opinion in the 5-4 decision, noted that the industry being regulated was involved in interstate commerce and that the law did not abridge freedom of speech or press or violate due process of law.

In addressing the First Amendment issue, Roberts observed that although the AP claimed to have discharged the employee for biased reporting, the record revealed the actual reason to be his union activity, which had no bearing on First Amendment issues: “The business of the Associated Press is not immune from regulation because it is an agency of the press. The publisher of a newspaper has no special immunity from the application of general laws. He has no special privilege to invade the rights and liberties of others.”

He noted that the AP could be held accountable for libel, punished for contempt of court, and subject to antitrust laws.

Dissent argued First Amendment rights, including of the press, were absolute

Justice George Sutherland authored a vigorous dissent concentrating on the First Amendment issues in a manner pleasing to absolutists and those who believe that the First Amendment should have a preferred position in the law.

He observed that whereas some liberties, such as due process, were qualified, “those liberties enumerated in the First Amendment are guaranteed without qualification, the object and effect of which is to put them in a category apart and make them incapable of abridgment by any process of law.

“That this is inflexibly true of the clause in respect of religion and religious liberty cannot be doubted; and it is true of the other clauses save as they may be subject in some degree to rare and extreme exigencies such as, for example, a state of war.”

Given such absolute status, the Court should be wary of any encroachment: “The destruction or abridgment of a free press . . . would be an event so evil in its consequences that the least approach toward that end should be halted at the threshold.”

In Sutherland’s judgment, press freedom “does not permit any legislative restriction of the authority of a publisher, acting upon his own judgment, to discharge anyone engaged in the editorial service.”

Dissent said publishers should be able to dismiss employees based on their opinions

Just as a judge might dismiss a juror for prejudice in a case, so, too, a news organization should be able to dismiss an employee that it perceives as too favorable toward labor.

Sutherland ended with a paragraph linking the First Amendment freedoms:

“Do the people of this land — in the providence of God, favored, as they sometimes boast, above all others in the plentitude of their liberties — desire to preserve those so carefully protected by the First Amendment: liberty of religious worship, freedom of speech and of the press, and the right as freemen peaceably to assemble and petition their government for a redress of grievances? If so, let them withstand all beginnings of encroachment. For the saddest epitaph which can be carved in memory of a vanished liberty is that it was lost because its possessors failed to stretch forth a saving hand while yet there was time.”

John Vile is professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.