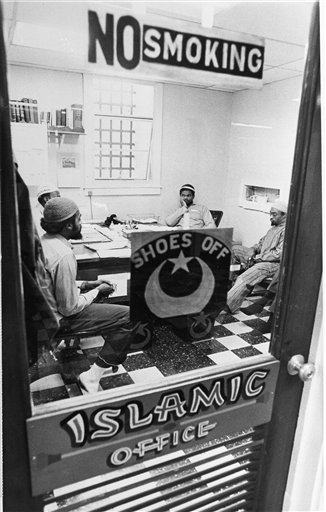

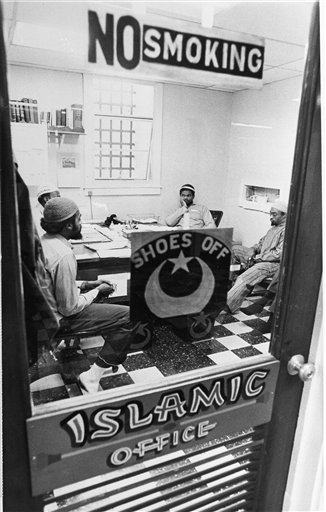

In O’Lone v. Estate of Shabazz,(1987), the Supreme Court, using a deferential standard of review for prison policies, held that inmate religious rights may be restricted for security concerns; the policies were not in violation of the free exercise clause of the First Amendment. In O’Lone, inmates in a New Jersey prison sued, alleging that prison policies that required some inmates to work outside the prison, and which barred these inmates from returning to the prison during the day, violated their right to free exercise of their Islam religion. The policies applied to all work-eligible inmates and were intended to minimize disruption and danger associated with moving inmates in and out of prison. In this photo, Muslim minister Abdul Shaheed holds his head in his hand as he talks to fellow Muslims in the Islamic office at the Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio, Jan. 9, 1973. Shaheed says at one time 104 men were attending his classes behind the penitentiary walls. (AP Photo/Steve Pyle, used with permission from the Associated Press)

In O’Lone v. Estate of Shabazz, 482 U.S. 342 (1987), the Supreme Court, using a deferential standard of review for prison policies, held that inmate religious rights may be restricted for security concerns; the policies were not in violation of the free exercise clause of the First Amendment. This holding led to several attempts by Congress to require that courts apply a less deferential standard of review in cases involving governmental interference in religion.

Inmates sued for not being allowed to return to prison during the day to participate in religious services

In O’Lone, inmates in a New Jersey prison sued, alleging that prison policies that required some inmates to work outside the prison, and which barred these inmates from returning to the prison during the day, violated their right to free exercise of their religion. These inmates wished to return to the prison during the day to participate in a

Muslim religious service. The policies applied to all work-eligible inmates and were intended to minimize disruption and danger associated with moving inmates in and out of prison. The U.S. district court had upheld the policies as reasonable security measures, but the U.S. appellate court had reversed on the grounds that the state should have to prove that there were no alternate measures that might accommodate the prisoners’ rights.