Accommodationism, sometimes called nonpreferentialism, is a constitutional doctrine asserting that the First Amendment promotes a beneficial relationship between religion and government. Accommodationism evolved from an interpretive method into a set of constitutional procedures applied when the Supreme Court faces questions of government involvement with religion.

Accommodationism is a way to interpret First Amendment

Jurists generally take one of three approaches — secularism, strict separation, or accommodationism — to interpret the First Amendment’s establishment and free exercise clauses concerning religion.

- Secularism has been defined as opposition to religion in the public arena. In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), Justice Hugo L. Black wrote that separatism asserts a “high and impregnable wall of separation” between church and state.

- Separatists find any law regarding religion in violation of the First Amendment. Accommodationism rests on the belief that government and religion are compatible and necessary to a well-ordered society.

- Accommodationists assert that in the First Amendment the framers intended to promote cooperation between government and religion, not neutrality or government hostility toward religion. They argue that because the establishment clause forbids Congress to make laws regarding “an establishment,” rather than “the establishment” of religion, government must not show preference among religions or the religious versus the nonreligious. According to accommodationists’ interpretation, the First Amendment permits governmental actions that promote religion, but not religious institutions.

Accommodationism arises in cases of public observance of religious holidays, symbols

Accommodationist arguments are usually made when the Supreme Court considers public observances of religious holidays or symbols or religious practice in public schools. Several justices have been accommodationists, including Byron R. White, William H. Rehnquist, Antonin Scalia, and Clarence Thomas. Many predict that Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. will follow in this tradition.

Most critics of accommodationism are secularists, such as Leonard Levy. These scholars argue that the original intent of the framers of the Bill of Rights was not to accommodate religion and government, but to keep each from influencing the other.

They reject the accommodationist position that the choice of the word “an” in “an establishment” of religion is critical to understanding the establishment clause. Separatists believe that a close exploration of the First Congress reveals the founders’ desire to erect a “wall of separation” between religion and government. Critics argue that nonpreferentialism introduces sectarian strife into politics, contrary to the goal of the First Amendment. They believe that the doctrine of accommodation to religion would inevitably entangle government with religion, harming both.

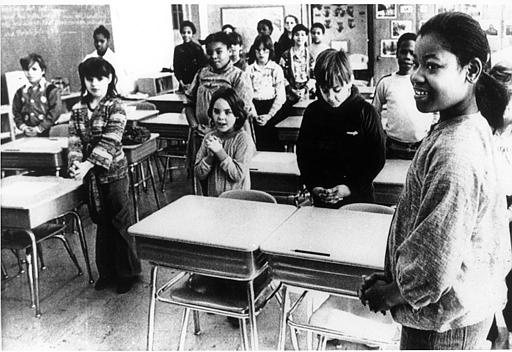

Prohibiting religious practice is among the Court’s most controversial activities. The Court has ruled that prayer, daily Bible readings, and religious training in public schools violate the establishment clause. In this photo, Terri Thompson, 11, leads her fourth grade class in a short prayer at the start of the day in a Boston public school in 1980. (AP Photo/Benoit, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Five tests used by courts to determine First Amendment religion claims

The Supreme Court generally applies some combination of five constitutional tests or doctrines when approaching questions of religious accommodation.

- First, the most well known of these is the three-pronged Lemon test, articulated in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), requiring that legislation have a secular purpose, neither promoting nor inhibiting religious practice, and that it not create excessive governmental entanglement with religion.

- Second, Courts try to “balance” the interests of the state with individual practice, as set out in Sherbert v. Verner (1963), which allowed a woman to receive unemployment benefits after being fired for refusing to work on her Sabbath.

- Third, courts consider whether legislation creates a direct or indirect burden on religion, as in Braunfeld v. Brown (1961) as well as Sherbert.

- Fourth, courts may consider whether the state has a compelling interest in abridging religious beliefs, such as pacifism, as in Gillette v. United States (1971) or exempting churches from property taxes, as in Walz v. Tax Commission (1970).

- Fifth, Courts apply strict scrutiny to any law or statute that offers direct or indirect benefit to religious institutions. Aside from Lemon, these tests derived from free expression cases.

The Court is most likely to accommodate free exercise claims.

As noted above, it has held that individuals cannot be denied unemployment benefits because their religion forbids working on a given day (Sherbert) nor be compelled to send their children to public school beyond the eighth grade, as established in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972). It has rejected claims by religious communities to be exempt from Social Security taxes because there is a compelling state interest in collecting the tax — United States v. Lee (1982). Courts generally also allow religious clothing, even in the presence of a dress code, except in some military settings.

Accommodationist arguments are usually made when the Supreme Court considers public observances of religious holidays or symbols or religious practice in public schools. In this photo, visitors to the Illinois State Capitol observe a privately funded nativity scene after entering the building in 2008. For the first time in state history, a nativity scene was on display inside the Capitol. According to state law, any expression of religion on government property must be funded and constructed by the private sector. (AP Photo/Seth Perlman, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Leglislation has sought to accommodate religion

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (FRFA) has sought to accommodate religion by requiring government to apply strict scrutiny in cases where governmental regulations interfere with the free exercise of religion.

Although the Supreme Court struck some provisions of this law as they apply to states, in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores (2014) it ruled that three closely held corporations whose owners had religious objections were exempt from financing certain forms of contraception under the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (better known as Obamacare) that they considered to be abortifacients.

Similarly in Zubik v. Burwell, 578 U.S. ____ (2016), the Court remanded similar cases to lower courts after seemingly finding a way that individuals could receive contraceptive coverage without implicating religious providers who opposed it.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Abercrombie and Fitch Stores, Inc., 575 U.S. ____ (2015) is another case related to religion accommodation. In that case, the Supreme Court ruled that an employer could be responsible for violating Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 for refusing to hire an individual who was wearing a head scarf, even though the employer had not specifically asked whether she was wearing the apparel for religious reasons.

Accommodationism risks violating the First Amendment

When Congress or state governments try to accommodate the sincere religious beliefs of citizens, they risk violating the establishment clause of the First Amendment or the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Nevertheless, the Court has held certain accommodations to be constitutional.

For example, in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Congress exempted religious organizations from the prohibition against discrimination in employment based on religious preference. Courts have also upheld voucher programs that provide for parents to spend state funds to send their children to public or parochial schools. The Court, however, held in Texas Monthly v. Bullock (1989) that religious publications and products sold across state lines are not necessarily entitled to tax exemption.

Accommodationism continues to vie with strict separationism as one of two leading theories of interpreting the religion clauses of the First Amendment. In this 2009 photo, Nebraska state senators stand during the prayer by the chaplain, on the opening day of a special session of the Legislature. (AP Photo/Nati Harnik, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court’s rulings prohibiting religious practice are controversial

Prohibiting religious practice is among the Court’s most controversial activities.

The Court has ruled that prayer, daily Bible readings, and religious training in public schools violate the establishment clause. The courts have held that public funds may be used to provide benefits, such as textbooks to students at parochial schools, but cannot provide educational materials to parochial schools directly.

Accommodationism and strict separationism are two leading First Amendment theories

Accommodationism continues to vie with strict separationism as one of two leading theories of interpreting the First Amendment. In practice, permissible accommodation depends upon the degree to which state action interferes with a central tenet of a religious doctrine and the degree to which the state’s interests are at stake.

Accommodation is a balancing act, seldom resolved by applying a single doctrine or test. In a pluralist society, such questions will continue to challenge the Court and citizens.

Dr. Michael P. Bobic, who worked as an assistant political science professor at Glenville State College in West Virginia, wrote this article in 2009. It was updated in 2017 by John R. Vile, professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. Bobic also is author of “With the People’s Consent: Howard Baker Leads the Senate 1977-1984.”