Ballot access refers to the basic rules and procedures that regulate whether and how candidates, political parties, and related matters such as ballot issues and referenda will be presented to voters for electoral consideration. The Supreme Court has ruled that state laws that make the process to get on a ballot unduly burdensome, particularly for third-party or independent candidates, infringe on the right of association that is protected by the First Amendment.

Ballot access provisions have been frequent sources of controversy in the United States because so much is at stake in elections.

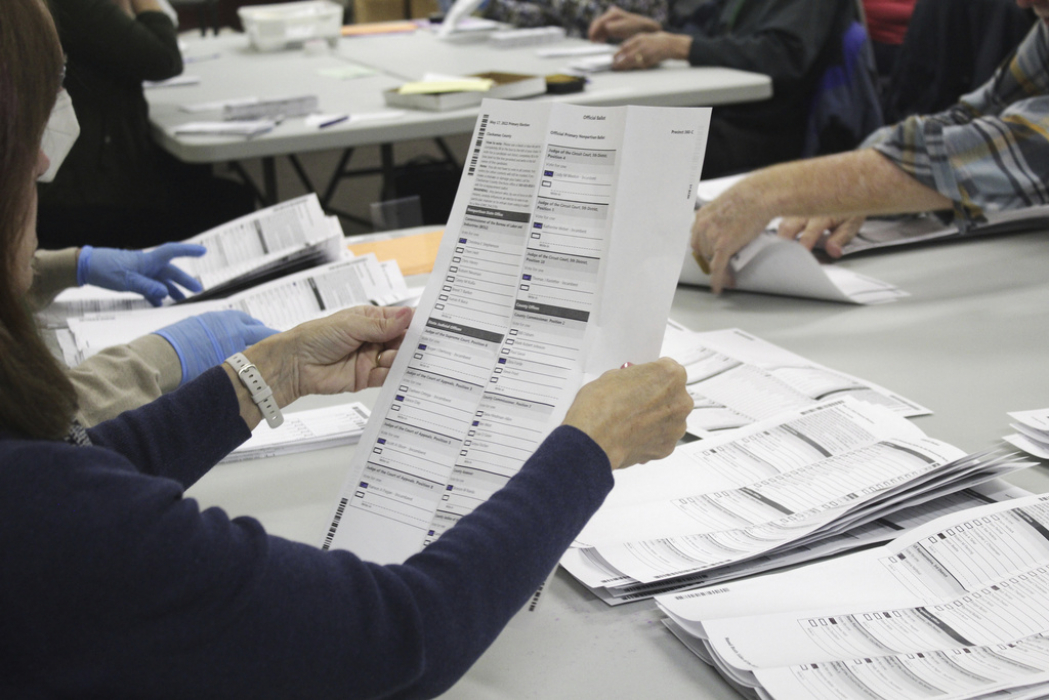

American voters did not use an ‘official ballot’ before 1880s

The U.S. Constitution decentralizes the election process to the states. Article 1, Section 4, of the Constitution states that “the Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the Legislature thereof.”

This deferral of election procedures to state governments has allowed each state to consider its own unique circumstances and conditions when designing the criteria for getting on the ballot. However, multiple amendments to the Constitution have, however, limited a state’s ability to limit who can vote in an election based on: race (15th Amendment, 1870); sex (19th Amendment, 1920); payment of a poll tax (24th Amendment, 1964); and age (26th Amendment, 1971).

Before the late 1800s, voters in the United States would either verbally inform election officials for whom they were voting or would place a ballot printed by their own political party in the ballot box. These practices tended to make the process prone to corruption, misinterpretation and inefficiency.

The Australian ballot, created in that country in 1858 and adopted by the United States in the 1880s, changed this design and allowed voters to cast their votes in secret for candidates on an office-by-office basis using an official ballot.

The new process not only ensured confidentiality but also made the election process more formal and credible. The Australian ballot model was thereafter used successfully in presidential elections, but voter turnout declined noticeably, because voters had to be able to read the ballot and literacy rates then were much lower than today.

The Australian ballot also affected which candidates could get on the official ballot, which until then, with no official ballot, had been relatively uninhibited.

In Williams v. Rhodes (1968), the Supreme Court invalidated Ohio’s law that made it virtually impossible for American Independent Party presidential candidate George C. Wallace, pictured here, to appear on the state’s presidential ballot. In this photo, Wallace listens to a question during a rally in Massachusetts in 1968. (AP Photo)

States set rules for getting on the ballot

States determine ballot rules. Many state governments delegate this responsibility to their county governments, which have elected or appointed “supervisors of elections.” Some local governmental bodies also set their own rules within basic parameters for local elections. The result has been extensive variability throughout the nation, not only in the criteria for getting on the ballot, but also in the ways in which elections are conducted.

Most states require candidates and parties that have not previously garnered a significant number of votes at the national level and that wish to appear on the ballot to collect a minimum number of signatures — often a percentage of the total number of registered voters. Similar provisions can apply for citizen-driven initiatives and proposed new laws and state constitutional amendments. Such requirements put minor parties and less recognized candidates at a disadvantage, as do some states’ imposition of “filing fees” to cover the costs of the ballot process. Another barrier to ballot access can be strict filing deadlines that are difficult or impossible for many “outsider” candidates and parties to meet. Incumbents usually have more money and resources to devote to the cause.

Restricting ballot access can limit discourse to two political parties

The predominantly two-party nature of the U.S. political system has fueled the ballot-access debate. Supporters of ballot-access restrictions view the matter from a practical standpoint, arguing that the established procedures and access criteria have deterred large numbers of unqualified candidates from appearing on ballots, thereby alleviating stress in the system and confusion within the electorate.

By contrast, reformers contend that stringent access criteria prevent competition and even alienate third-party candidates who are unable to collect the requisite number of signatures to appear on the ballot. In addition, such candidates must contend with the name recognition that gives incumbents of the two major parties a distinct advantage.

Political apathy and uninterest in elections further diminish the likelihood that a qualified newcomer will be able to meet access criteria.

Such criteria stifle the political dialogue and limit discourse to those issues favored by the two major parties. Finally, reformers contend that by narrowing the field of new and entrepreneurial candidates, ballot-access restrictions reduce the quantity and quality of choices available to voters, and thus have contributed to the declining levels of voter turnout.

Supreme Court: Ballot access cannot be unduly burdensome

The right of candidates and political parties to be on the ballot is not unlimited. However, because this right implicates the freedom of association, courts have ruled that the government’s authority to regulate elections cannot make the process for getting on the ballot unduly burdensome.

In Williams v. Rhodes (1968), the Supreme Court invalidated an Ohio law that made it virtually impossible for American Independent Party presidential candidate George C. Wallace (the former Alabama governor) to appear on the state’s presidential ballot. Ohio law required that candidates collect a large number of signatures and that parties form committees well in advance of the election.

In Bullock v. Carter (1972), the U.S. Supreme Court found that the payment of an expensive filing fee to run for office was unconstitutional. The Court said the fees fall “with unequal weight on candidates and voters according to their ability to pay the fees, and therefore it must be ‘closely scrutinized’ and can be sustained only if it is reasonably necessary to accomplish a legitimate state objective, and not merely because it has some rational basis.”

Conversely, in Storer v. Brown (1974) the Court upheld a state law requiring an independent candidate running for office to demonstrate disaffiliation from a party for a least one year. But in Anderson v. Celebrezze (1983) the Supreme Court invalidated on First Amendment grounds a state law that imposed early filing requirements for an independent presidential candidate who wished to appear on the general election ballot.

Court scrutinizes laws on signatures required for third-party candidates

Often, independent and third-party candidates are required to collect and file a minimum number of signatures to appear on the ballot. If that minimum threshold is too high, the courts may invalidate the requirement as unconstitutional, burdening the association rights protected by the First Amendment.

In Illinois State Board of Elections v. Socialist Workers Party (1979), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a state law requiring independent party candidates to obtain more signatures to be on Chicago’s ballot than to be on a statewide office ballot was unconstitutional. Later, in Norman v. Reed (1992), the Court struck down another Illinois law requiring new third-party candidates for statewide office to collect 25,000 signatures, sometimes in multiple political subdivisions, and to meet other procedural hurdles.

In Munro v. Socialist Workers Party (1986), the Court upheld a requirement that a party secure at least 1% of the vote in a primary to gain a spot on the general election ballot. The Court noted that although the 1% requirement did impinge upon association rights of the party, these rights were not absolute and it was not burdensome to require the party to demonstrate some minimum level of support to appear on the ballot.

In Timmons v. Twin Cities Area New Party (1997) the Court upheld, against a First Amendment challenge, a state “anti-fusion” law barring a candidate from one political party from appearing on the ballot as an endorsed candidate for another political party. The Court’s reasoning here was that the compelling interest in preventing fraud and voter confusion outweighed any First Amendment claims to ballot access.

Overall, although the courts have been hostile to the payment of fees to obtain ballot access, other requirements in place to demonstrate that candidates or political parties have sufficient political support have been upheld as legitimate governmental interests in regulating elections.

Initiative and referenda items also create controversy

Many states also have procedures that allow voters to engage in “direct democracy” very much in the First Amendment spirit of the right to petition the government. They can vote new laws into being that may bypass the normal legislative process or make recommendations to legislators. In states such as California, voters have passed a wide variety of “propositions” for many decades.

At local levels, direct voting on subjects such as bond issues, amendments to city charters and related matters are quite common.

Here, too, laws regarding how such measures go before voters come into play. According to the Ballotpedia website:

Every state but Delaware allows citizens to vote on legislatively referred constitutional amendments, and 23 states allow citizens to vote on legislatively referred state statutes…The ballot initiative process is used by 26 states, as well as Washington, D.C., and 18 of those states allow voters to initiate constitutional amendments. Constitutional conventions can also be used to put ballot measures before the people.

To address these matters, states have laws regulating how these matters get to ballots with varying requirements for how many signatures are required on petitions to get onto the ballot, where and how such signatures may be obtained, what constitutes a legal signature on a petition, what is legal versus illegal language for a ballot initiative and what are the deadlines to obtain signatures, submit ballot language for approval and so forth.

Elected officials sometimes resist efforts to bypass the legislative process and are accused of making it unreasonably difficult for initiatives to go directly to voters. As a result, petitioning laws and regulations have sparked lawsuits and court cases. For example, in 1999, in Buckley v. American Constitutional Law Foundation, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a Colorado law requiring that petition circulators be registered voters in the political jurisdiction in which signatures are being solicited

This article was originally published in 2009. Daniel Baracskay teaches in the public administration program at Valdosta State University. It was revised in 2023 by Dennis Hetzel with changes to include the material on ballot initiatives and referenda. Hetzel has been a reporter, editor and newspaper publisher, executive director of the Ohio News Media Association and president of the Ohio Coalition for Open Government.