The Supreme Court’s decision in Golan v. Holder, 565 U.S. 302 (2012), upheld U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder’s defense of a U.S. copyright law against challenges brought by orchestra conductors, musicians, publishers, and others. The U.S. copyright law in question had taken previously available material out of the public domain. The Court used the U.S. Constitution’s Copyright and Patent Clause and the First Amendment to make their decision.

Copyright was extended to works that had previously lacked protection

In Section 514 of the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (URAA), which the U.S. adopted in 1994, the U.S. extended copyright protection to foreign works that had previously lacked U.S. protection. These works had not been protected in the U.S. at the time of their publication because they were sound recordings made before 1972 or because the authors had not met certain U.S. legal technicalities.

This law meant that petitioners like Lawrence Golan, a conductor, would have to pay for materials that were previously considered to be in the public domain. However, Section 514 did not assess any liability for prior use of such works.

Courts determined law was constitutional

Initially, a U.S. District Court granted the attorney general a motion for summary judgment against petitioners, but the Tenth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that while the regulations did not violate the copyright and patent laws, the First Amendment issue deserved further scrutiny. The case was remanded to the District Court.

The District Court decided that because the law did not regulate materials on the basis of their content, the law would be upheld if “narrowly tailored to serve a significant public interest.” However, the court gave petitioners summary judgment on the basis that the government had not shown that the law advanced such interests.

The Tenth Circuit again reversed, determining “that the law was narrowly tailored to serve the important government aim of protecting U.S. copyright holder’s interest abroad.”

Copyright and Patent Clause and First Amendment used in decision

In affirming this decision for the Supreme Court, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, writing for six justices, examined both the Copyright and Patent Clause of the Constitution and the First Amendment.

In examining the former, she noted that the text of the clause did not deny authority to Congress to withdraw works from the public domain. Moreover, she noted that the decision in Eldred v. Ashcroft (2003) had allowed for the extension of copyrights. Also, the Copyright Act of 1790, as well as subsequent acts of private bills, had granted protection to works that were previously within the public domain.

Eldred had recognized that every copyright imposes some restriction on expression. However, rights remain protected by the dichotomy between ideas and expression, because only the second receives copyright protection, and by “fair use” provisions for educators and others. Eldred thus failed to impose heightened review in such cases.

Ginsburg concluded that Congress could “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts” by enacting systems of copyright protections.

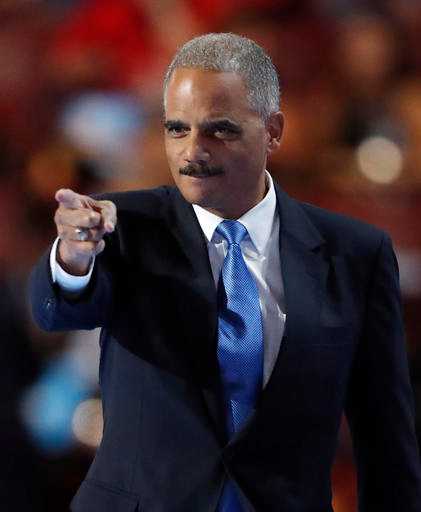

Eric Holder, former U.S. attorney general (AP Photo/Paul Sancya, Used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Congress had extended copyright protections previously

Ginsburg rejected ideas that the petitioners in this case had “vested rights” in works that were already in the public domain, which she considered to be simply an argument “to achieve under the banner of the First Amendment what they could not win under the Copyright Clause.”

Congress had previously extended copyrights to foreign works in 1891, to dramatic works in 1856, to photographs and photographic negatives in 1865, to motion pictures in 1912, to fixed sound recordings in 1972 and to architectural works in 1990. Ginsburg thus rhetorically asked, “If Congress could grant protection to these works without hazarding heightened First Amendment scrutiny, then what free speech principle disarms it from protecting works prematurely cast into the public domain for reasons antithetical to the Berne Convention?”

The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works was an international copyright aggreement that took effect in 1886. The United States joined in 1989.

Acknowledging potential problems with orphan works, she believed that this was a matter for congressional rather than for judicial action.

Dissenters were concerned about copyright powers

Justice Stephen Breyer wrote a dissent joined by Justice Samuel Alito. Contrary to the aims of the copyright clause, Breyer did not believe this law provided writers with incentives to create any new works. He traced copyright statutes back to the Statute of Anne in 1710 and noted reservations among American Founders like Jefferson and Madison about the length of copyright protection.

Breyer thought that American copyright laws were largely based on utilitarian considerations designed to focus on new production. The law at issue allowed restored copyright holders to impose fees that consumers previously got for free and raised administrative fees on potentially millions of works.

Although agreeing that the law does not discriminate on the basis of subject matter, Sorrell v. IMS Health, Inc. (2011) had established that this did not exhaust First Amendment inquiry. By “restricting the use of previously available materials, reversing payment expectations; [and] rewarding rent-seekers at the public’s expense,” this law raises valid First Amendment issues, which are important enough for courts to scrutinize.

Breyer expressed similar concerns about copyright powers and questioned the precedents cited in the majority opinion. He concluded that the government did not use the “least restrictive methods of compliance that the [Berne] Convention itself provides.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2017.