Wheaton v. Peters, 33 U.S. 591 (1834), was one of the first cases to deal with copyrights, the protection of which is an exception to general First Amendment protections of freedom of speech and press.

The Court rejected the idea that there was a federal common law on the subject or that cases could themselves be copyrighted and remanded the case to determine whether state common law applied to case notes and commentary.

In early copyright case, author sued publisher for selling reprints of Supreme Court decisions

Henry Wheaton, the author of 12 volumes of reports of Supreme Court decisions, sued Richard Peters for selling a reprint of the volumes, which Wheaton alleged violated his original copyright. Peters countered that Wheaton had not properly followed legal requirements for securing such copyright.

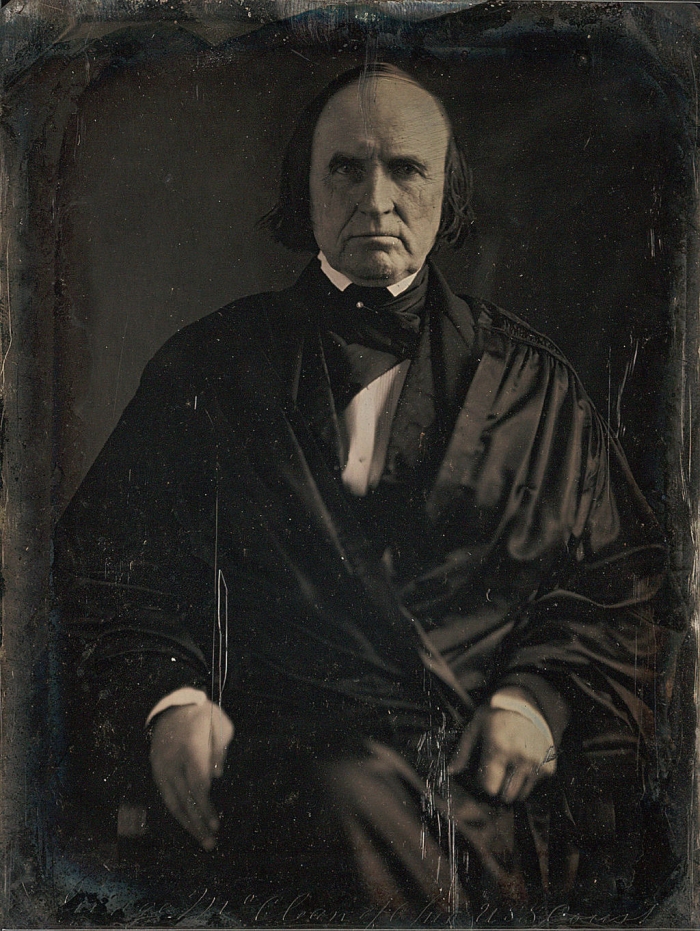

Justice John McLean wrote the opinion for the Court, which canvassed British, state, and federal law. McLean said that English common law recognized the right of authors in their works although this law had been somewhat modified by statute.

Supreme Court: No common right of copyright

McLean wrote, “It is clear that there can be no common law of the United States” since “There is no principle which pervades the union and has the authority of law, that is not embodied in the constitutional or laws of the union.” Hence, “The common law could be made a part of our federal system, only by legislative adoption.”

Such common law could be embodied in the legal systems of individual states. Moreover, the national government had adopted a copyright law in 1790, which it had modified in 1802. The latter law required authors to publish notice of their copyrights in newspapers and to deposit a copy of their works with the Department of State.

Justice McLean: Court opinions cannot be copyrighted

McLean remanded the decision to the circuit court for a jury to determine whether Wheaton had complied with the terms of the law.

In words that have been important for the concept of a public domain, he ended by observing that “no reporter has or can have any copyright in the written opinions delivered by this court; and that the judges thereof cannot confer on any reporter any such right.” G. Edward White (1991) observed that this statement “reduced the Reporter’s office from a literary position to that of a recording secretary” (p. 421).

Dissenters thought state had common law of copyright

Justices Smith Thompson and Henry Baldwin dissented.

Thompson thought that the right of copyright was traceable to the common law of England and did not believe the Statute of Anne had been recognized in Pennsylvania. He surveyed early state and federal laws that recognized such a privilege. He did not think it was necessary to reach the issue of whether there was a general common law in the United States since he believed it was established in Pennsylvania, where Wheaton had obtained his original copyright. Thompson also did not believe that later statutes were designed to make the assertion of such common law rights more difficult, and he would accordingly enforce this right on Wheaton’s behalf.

In 1838 a jury found that Wheaton did have copyright rights to his notes and appendices. After both Wheaton and Peters were dead, the latter’s estate paid the former $400 (White 1991: 422).

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.